One advocate’s guide to better healthcare treatment.

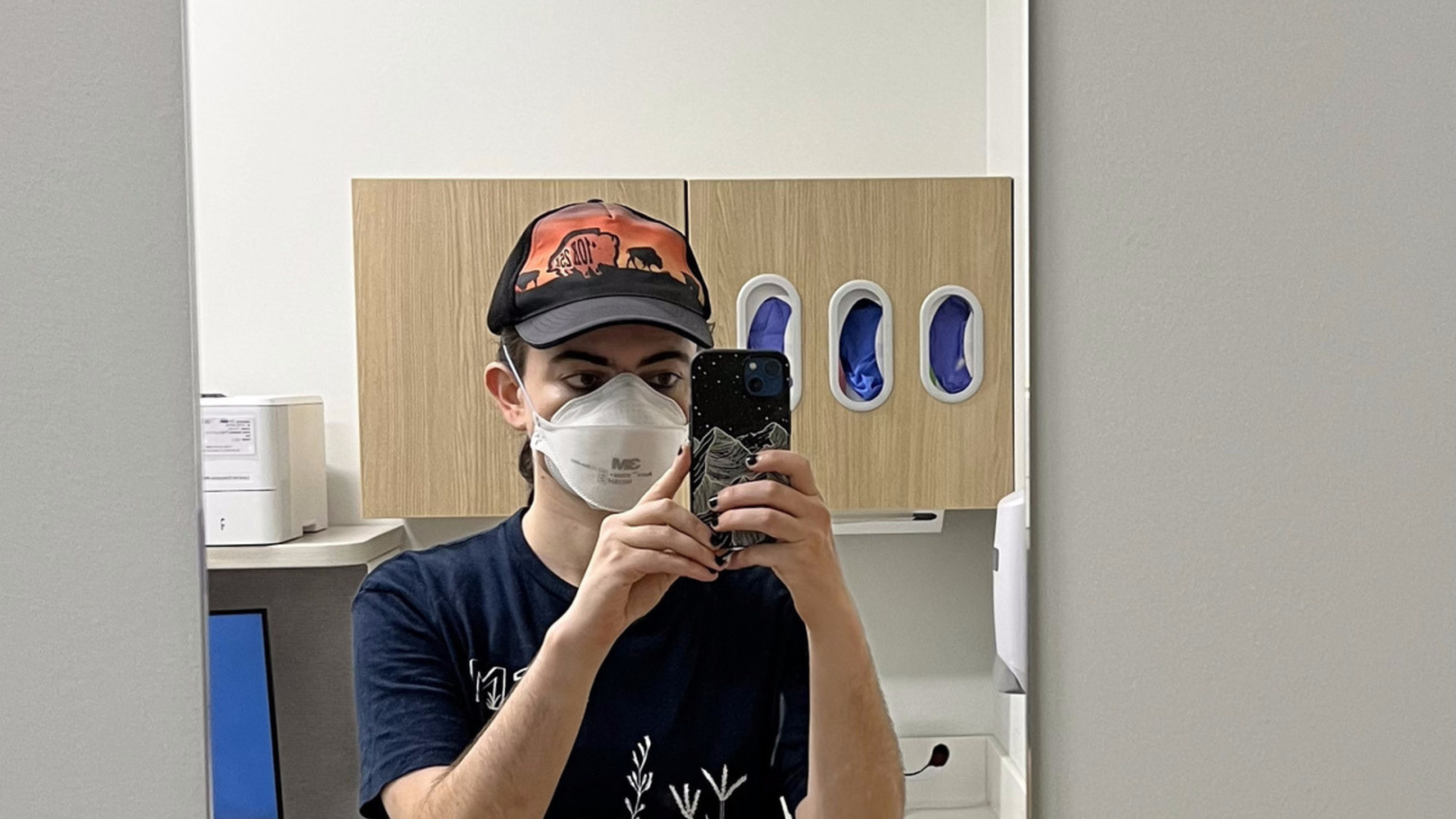

Sam Sharpe

Intersex people have all of the same health care needs as non-intersex people, as well as some specific intersex care needs. However, due to the ongoing erasure and stigma of bodies like mine that don’t conform to the sex and gender binary, getting any kind of care can be confusing, difficult, and scary.

This is what the healthcare I need looks like.

Some of the things I need are fairly straightforward.

I need to be respected, listened to, and treated like a person, not an annoyance or an anomaly. I need to be able to be heard when I describe my experiences, goals, and concerns, and have them taken seriously.

Some of the things I need should be simple but are not.

I need my healthcare information to be collected, stored and transmitted consistently and correctly.

I need my records to be sent between facilities when they say they will be (for some reason this seems to rarely happen). I need providers to read my records before meeting with me and listen to my explanations and not make assumptions.

I need forms that ask accurate and relevant questions about sex traits so that I can provide accurate and relevant answers. The (bad) default is “What is your gender? Options: Male or Female.” (Those are not genders and I am neither). Sometimes there are separate questions for sex and gender with slightly better options, but which still don’t capture the complexity of being both transgender and intersex. Recently, some offices are trying harder but still missing the mark with questions like “What was your legal sex assigned at birth? Male, female, or intersex.” (I was not legally assigned intersex at birth. Virtually no one is.)

Intersex status usually isn’t reflected in legal or original birth certificates or even the most inclusive question about gender. There isn’t a consensus about the best way to capture the highly variable ways that people can be intersex and relate to their intersex variations. One place to start is providing a separate, optional question about whether a patient is intersex or was born with variations of sex characteristics. Depending on the context, an organ inventory (asking what body parts someone currently has) is an important way to get accurate information and avoid harmful assumptions.

“I need healthcare providers to treat the problems I am having, not the ones they think I should want to solve.”

I need my name and pronouns to be used correctly in every healthcare interaction. I have had at least three different pronouns used for me by healthcare providers, sometimes all within one visit.

I need providers to engage with my gender and intersex status without being actively harmful or impossibly weird about it.

Nurse: “Do you still get periods since starting the testosterone?” (I have never been on testosterone?)

Nurse: “Are you a transgendered male?” (no??)

Cardiologist: “Are you aware that you have a mustache?” (yes???)

Endocrinologist: Attempted to coerce me into starting spironolactone for aesthetic reasons and then billed insurance for “hirsutism.” (why????)

I need healthcare providers to treat the problems I am having, not the ones they think I should want to solve. If I ask for help with specific symptoms related to my intersex variation like low Vitamin D and painfully dry eyes, I do not want to be counseled on achieving what is presumed to be desired fertility and aesthetic femininity.

Some of the things I need are in fact complicated, because I am complicated, but that does not mean I deserve worse care.

I need healthcare that does not indiscriminately blame all of my physical and mental health problems on the perceived pervasive pathological deviance of my intersex status. At the same time, I do need healthcare which understands that my intersex variation has far-reaching and systemic health implications. Hormones have intricate and complex impacts on physical and mental health, and only through my own research did I discover that my variation is likely related to many of the other physical and mental health complexities I have experienced.

I need healthcare which understands my body will never look or function exactly like a non-intersex person. That means that trying to make my body not intersex is not a viable or helpful option, but neither is assuming that my well-researched healthcare goals are impossible because I am intersex.

I need healthcare that can come from a place of informed creativity. Oftentimes, within medical training and systems, there are specific, distinct standards, reference values, settings, etc. for cisgender endosex (not intersex) male and female bodies. Those standards may not make sense for me. There is no universal “intersex” standard because we are all so different, even those of us with the same variations. It’s a puzzle, but that is ok if healthcare providers are interested in solving it with me.

I do not need every provider to be an expert on my intersex variation. I have a poorly understood and highly variable condition that researchers are still trying to understand. I need to have access to specialists who are competent and well versed in what we know so far about this variation, but who can also individually evaluate me on both clinical indicators and my subjective experience. I need access to interventions that are supportive of my needs and goals in relation to my intersex variation, but I do not need to be overmedicalized or pathologized because of it.

I need non-specialists to know what my variation is (it is not uncommon) and to not harbor harmful misconceptions about it (also unfortunately not uncommon). I need them to consider its impact when it may be relevant and collaborate with specialists if necessary.

I need healthcare providers to respect that I am the expert of my own identity and experience of my body. It is fair for providers to ask me about my sex traits and gender identity as it is relevant to my care. It is not fair for providers to ask irrelevant and invasive questions about my perceived “differentness” to satisfy their own curiosity. It is not fair to expect me to be an expert on sex and gender and provide comprehensive education about these topics when I am presenting for care. I happen to be an expert on these topics because they are of interest to me and I have the immense privilege of studying biology and gender studies in graduate school. It is not a fair or reasonable expectation for all intersex and trans people to have this expertise and be willing to dispense it at any time. I need to be able to be a patient, not a professor.

Finally, I need healthcare to be safe. I am scared at every visit, especially with new providers or in the ER, about how my sex and gender will be perceived and how I will be treated because of it. I am afraid I will receive awkward comments, invasive questions, or worse, compromised care because providers will be confused or disgusted by my intersex body. I don’t know how my legal name and legal sex will be interpreted in contrast to my unexpected sex traits and illegible gender presentation. I don’t know when it is safe to ask for the correct name and pronouns to be used. It feels shitty to be referred to as a name and gender I am not, but less shitty than when I try to provide corrections and get ignored or met with hostility.

It is unfortunately rare that I actually encounter healthcare which meets all of these needs.

But it has happened. Recently, a new provider requested my childhood growth charts, then asked me to share as much detailed information as I was comfortable with about my intersex traits and history of gender transition. She told me that comparing my charts to the male and female standards would lead to drawing different conclusions about my current health status, and she wanted to know which one would be more accurate based on my understanding of my current sex traits and development during puberty.

The choice between two binary options is still imperfect, but it made a world of difference to have a provider ask which one I thought would fit better and explain what that would mean.This well-handled intersex-care interaction was so rare and startling that I had to stop and tell the provider how correctly she had approached my case before answering her questions.

Hopefully someday this type of attentive and appropriate care will be the standard, rather than an extraordinary exception.

Medical providers can start their journey to intersex education with our brochure What We Wish Our Doctors Knew, our Intersex Affirming Hospital Policy Guide with Lambda Legal, and Affirming Primary Care for Intersex People with the National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center.