Courtney at 4 years old, deep in their microbang era, smiling alongside their favorite stuffed animal.

Courtney Felle (they/them) is a 2024 interACT Youth Cohort Member and a current PhD Student in Disability Studies and Writing, Rhetoric, and Literacy at the Ohio State University. They are passionate about disability theory, creative writing, fiber arts, and bad reality TV—and constantly angry about diagnostic injustice. Find them on Instagram via @courtneyfelle. You can learn more about CAH and other intersex variations in our glossary.

Try Googling “POR Deficiency” right now. I’ll wait.

You’re overwhelmed, right? You found a few pages of scientific articles, littered with highly technical jargon and published by organizations with names as reassuring as “Rat Genome Database.” You found case studies from four anonymized South Korean patients. What you did not find, anywhere, is human emotion. Human experience. Human narrative.

I discovered that I have POR Deficiency from online genetic testing results. Sitting alone in my living room, I felt confused, relieved, apprehensive, and perhaps most importantly, uninformed. I wanted answers the internet could not provide, so while I imagined others out there, those fellow patients remained theoretical only.

So here I am. I want to pop up when you Google POR Deficiency: in plain language, with all the messy feelings and reactions that come with being human.

My Symptoms with POR Deficiency

I have a “moderate” version of POR Deficiency. When I was 13 (that is, when I started puberty and all the lovely hormone changes that come with it), I began having daily headaches and joint instability a la comorbid hypermobility. I had a few episodes of suddenly fainting while at school or in volleyball practice, freaking out my classmates. Over time, I struggled to adjust when the temperature changed and felt vaguely dizzy, nauseous, and in pain all the time.

I didn’t get my period until I was 16, a fairly late age. Even now, I only get my period once every 4-6 months. While this sounds great in theory (I’m so sorry to uterus-havers with painful periods every month!), having a period less than once every three months comes with significantly higher lifelong risk of ovarian cancer, which already runs in my family.

I also have a funky manifestation of POR Deficiency as temporary paralysis, up to my full body, due to a sudden shift in potassium levels internally. The fancy name for this is secondary hypokalemic periodic paralysis. My cells can’t shift potassium in and out properly, as the process requires more POR than I can make. When faced with sudden stress, such as an unexpected shock or emotional argument, my muscles can shut down. This ranges from an inability to move my hands and legs all the way to an inability to even lift a finger, speak, or in severe cases, breathe, since the diaphragm is a muscle.

Paralytic episodes can also happen due to sudden shifts from cold to warm temperatures, when cooling down from physical exertion, and upon eating sugar, which I have had to significantly limit (to varying success for an admitted dessert lover). Even between full-body attacks, I have muscle weakness and heaviness that can make it difficult for my body to bear its own weight. I also have highly painful muscle spasms in my right thigh.

Courtney at 11 years old on a family beach vacation.

What is POR Deficiency?

Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency, or POR Deficiency, is a rare condition that does not neatly fit into one medical specialization. Due to a genetic mutation, individuals with POR deficiency do not produce the standard level of POR, a protein that is key to many fundamental internal processes. This lower level of POR affects the body’s ability to produce energy (also known as metabolism) and to regulate hormones, including sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone as well as other hormones like cortisol that are released with stress. (The Pandey lab has published good overviews of POR Deficiency, including this one.)

Estrogen and testosterone, two major sex hormones

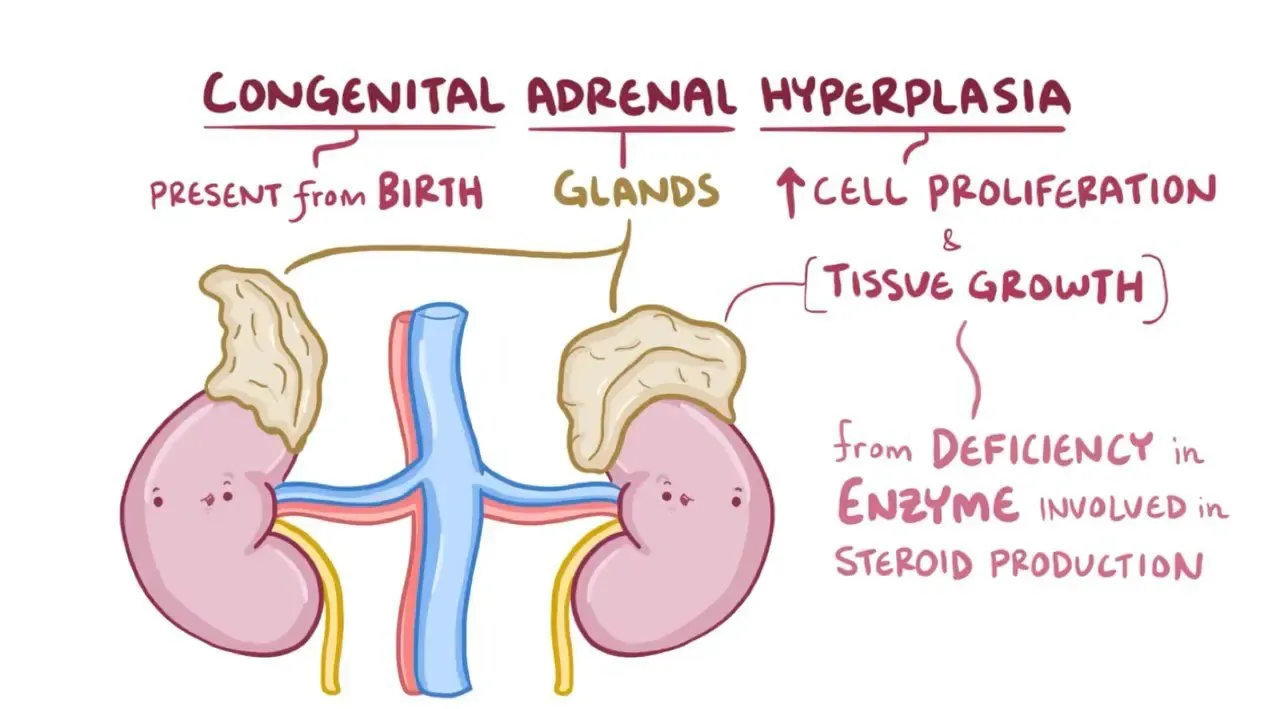

POR Deficiency is considered a rare version of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH), another condition under the intersex umbrella. However, unlike more common forms of CAH, including both classic and nonclassic forms, POR Deficiency does not directly impact 21-hydroxylase and differs in symptom presentation. Scientists discovered POR Deficiency recently in 2004, and since it impacts hormones (making it an adrenal condition), they sorted the diagnosis under CAH.

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)

Image: Osmosis

About 140 patients worldwide have a confirmed case of POR Deficiency. This is really small. As much as my mom joked when I was a kid that I was one in a million, statistically I’m now 1 in fifty-eight million. You could multiply the number of current patients with POR Deficiency worldwide by over 37,000 and it would still be considered a rare disease by the World Health Organization. Rare intersex variations of all kinds exist and matter!

That said, the only method that can diagnose POR Deficiency at present is Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), a type of genetic testing that looks comprehensively at nearly all of your genes. The vast majority of individuals alive today cannot access WGS due to the cost, access, and administrative barriers associated. Although (nondisabled) people don’t typically link “privilege” with an ultra-rare genetic disability, I am incredibly privileged to have accessed genetic testing to confirm my POR Deficiency diagnosis. Likely, with equitable availability of genetic testing, the amount of people who truly have POR Deficiency worldwide would be much higher than 140.

Types of POR Deficiency

POR Deficiency can be “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” Keep in mind that these are designations by doctors and researchers, so they do not necessarily describe how much POR Deficiency affects a person’s life, only their proximity to significant medical risk and/or fatality.

Those with “severe” POR Deficiency are diagnosed at birth more often due to a distinctive skeletal shape (Antley-Bixler Syndrome, ABS). Typically, if someone has ABS, more organs are affected to a more significant degree, including heart abnormalities, kidney abnormalities, cognitive disabilities, and hearing loss/Deaf gain. Most patients in this category are assigned male at birth.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, “mild” POR Deficiency does not present with visible skeletal differences. Many times, patients experience delayed puberty and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) symptoms but otherwise do not notice the effects of POR Deficiency. (As the prevalence of PCOS may suggest, most people with “mild” POR Deficiency are assigned female at birth.)

Antley-Bixler Syndrome (ABS)

Image: Learn Medical Genetics

Because of this, it is likely that many people with POR Deficiency go their whole lives without ever knowing their true, underlying diagnosis. For example, while PCOS can be a diagnosis in itself, it can also be a symptom of other conditions such as POR Deficiency. This knowledge can be crucial for making informed health decisions, and it underscores why it’s pragmatically impossible to exclude people with PCOS from the term “intersex.”

Those who are diagnosed with “mild” POR Deficiency often discover it somewhat indirectly due to fertility struggles and related genetic testing when trying to become pregnant. (Not uncommon to mild forms of nonclassic CAH more broadly!)

In the middle, there are “moderate” cases of POR Deficiency. Patients may not have skeletal differences or serious organ abnormalities, but POR Deficiency produces symptoms beyond only the reproductive system, which might involve hormone dysregulation, metabolic difficulties, and general symptoms known to fellow chronically ill folks such as chronic pain, fatigue, and dysautonomia.

My Life with POR Deficiency

Beyond the obvious symptoms, POR Deficiency affects my life in a variety of ways. The struggle to get diagnosed has fundamentally shaped my personality and my politics. I wasn’t properly diagnosed with POR Deficiency until age 24, over a decade after my first noticeable symptoms. Doctors repeatedly dismissed my concerns, either unable or unwilling to properly treat a young femme with mysterious, systemic issues.

Courtney and fellow intersex activists Dez Edwards and Ly Chayim show off their mobility aids at the 2024 interACT Youth Healing & Wellness Retreat. Read more on intersex variations and disability advocacy from Ly here.

Finding out that POR Deficiency is an intersex variation adds a layer. I had already suspected that I was intersex because of my symptoms as well as my personal relationship to genderqueerness, but doctors were more willing to let me continue to struggle with undiagnosed and untreated pain, fatigue, and paralysis than even consider that I might be intersex. That’s how deep stigma runs! Unbeknownst to doctors, I was grateful to learn more about myself and my experiences through understanding myself as intersex.

As I figure out the best treatment plan and collaborate (hopefully) with doctors to achieve it, I’ve cobbled together various supports. I use different mobility aids based on which symptoms I am experiencing each day. I have a cane, forearm crutches, a manual wheelchair, and a lightweight, mint green, folding travel power chair nicknamed Pepper. Muscle weakness and pain are the most evident reasons for my mobility aids, but it is also helpful to have Pepper on long excursions out of the house in case I begin to have a paralytic episode.

I also wear a medical alert bracelet that reads “Periodic Paralysis, Do Not Move, Do Not Call 911.” The last thing I want if I experience paralysis in public is to get roughhoused by cops or EMTs when I am physically unable to respond. At least this way, people know my preferences and basic information. I have crisis plans shared with friends. I also have medical information and contacts stored in my phone’s Emergency ID, and I keep oral potassium chloride and a health insurance card on me constantly.

My Advocacy with POR Deficiency

My first foray into advocacy was through disability movement spaces. I didn’t yet know what my diagnosis was, let alone that it would be an intersex variation, but I did know after many years of overcoming internalized ableism and imposter syndrome that I experienced my body and the world as a disabled person.

I connected with others who understood everything that came with being chronically ill as a teenager: fighting my school for accommodations, feeling frustrated after another dismissive doctor’s appointment, and wondering what my life would be like if I didn’t have the “normal” progression of growing up. It was a relief. I had a community, and we were moving together toward the future we wanted instead.

Following my POR Deficiency diagnosis, I reached out to interACT and became involved as a 2024 Youth Advocacy Program cohort member. I messaged other intersex friends and comrades. I read what I could find on intersex history and resistance. (I highly recommend Pidgeon Pagonis’s memoir, Nobody Needs to Know.)

It is so helpful to feel part of a community bigger than yourself. People have come before you and paved the way, and people will come after you for whom you can pave the way.

Courtney pointing proudly to their intersex flag shirt while using Pepper at the 2024 DC Dyke March.

What Next?

This is only an introductory explanation to POR Deficiency and the start of my intersex advocacy journey. There is so much to still come. I have an entire life to understand what having POR Deficiency means to me. Right now, I am hopeful, I am loving, I am loved, I am proudly intersex, and I am confused and mediocre in the way most 24-year-olds are. I am reclamatory, I am capable, I am usually in pain, and I am not interested in some alternate, stagnant life I could have had without POR Deficiency. At risk of sounding corny, I have POR Deficiency as much as I have low-POR richness. Whether you have POR Deficiency, love someone who does, relate to having a rare or misunderstood intersex variation, or resonate with other parts of this story, we will have a future together. I look forward to seeing you there.

interACT believes every intersex person deserves justice, and that only through ending interphobic legislation and intersex medical harm can we find justice under the law. You can help create a different future for intersex youth by giving here.