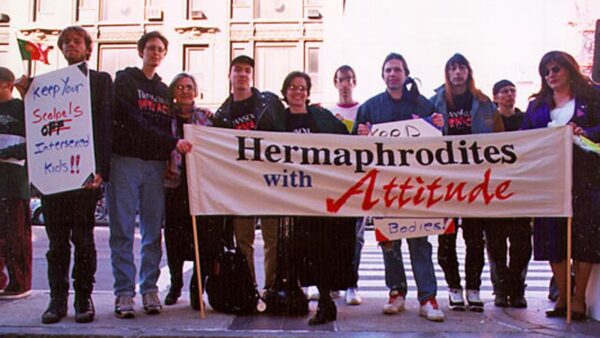

At the first ever public intersex rights demonstration in 1996, intersex activists Max Beck and Morgan Holmes were joined by their allies outside the American Academy of Pediatrics annual conference in Boston to demand an end to nonconsensual, non-emergent surgeries on intersex children. This 1996 protest, along with the then-emerging intersex rights movement, represented an attempt to shatter the false yet widespread belief that intersex children could and should be “cured” of being intersex through surgery. As intersex activist and writer Emi Koyoma writes, according to this perspective, “by definition intersex adults do not exist,” and, instead such “cured” children will grow up to be “a bunch of ‘formerly intersex’ patients.”

This set of beliefs is still dangerously present in many laws and hospitals. However, we know that, regardless of what medical interventions they are subjected to, intersex children cannot be made into non-intersex adults, and they deserve the opportunity for intersex futures free from medical harm and coercion.

To make such futures possible, we will need to see changes to state and federal legislation, medical ethics, and standards of care for people born with sex trait variations. But I think we also need something else, not just from doctors and lawyers and politicians, but from everyone.

“Hermaphrodites With Attitude, Boston, 1996.”

The first time I felt ready to share my experiences of sex and gender publicly online, the working title of my article during the pitching and editing process was “My hyperandrogenized trans body does not exist.” As an intersex adult, in the words of Koyoma, by definition I cannot exist. And yet, I know and believe I am possible. To bring about a liberated intersex future for me and millions of others intersex people, I need you to believe it too.

In order to achieve this liberated future, we need to start by knowing our history.

Intersex children and attempts to “normalize” them

The practice of attempting to medically ‘cure’ intersex children of their sex trait variations which Beck and Holmes protested in 1996 was developed from a model introduced in the 1950s. Psychologist John Money developed the “optimal gender of rearing” (OGR) model in an effort to remove the appearance and functional impacts of intersex traits from children. According to this model, a combination of early surgery, raising children with strictly enforced, normative gender roles, and lying about or concealing an intersex child’s medical history would produce socially successful, gender-conforming, ‘formerly intersex’ adult men and women. Doctors believed that the OGR protocol would prevent intersex adulthood and eliminate the possibility of intersex futures.

This model was not created in a sterile medical vacuum, free from societal biases. Instead, the model emerged from and proceeded to further promote a cultural standard that found the possibility of intersex futures threatening and unthinkable. This standard aimed to shape society, science, and even bodies themselves in its own image, enforcing the belief that sex and gender always naturally aligned in one of two ways. And for anyone born with sex characteristics that varied from these paths, the model would ensure they were swiftly and permanently directed onto one of them.

This cultural standard often remains invisible, and as a result, has come to seem inevitable—erasing intersex people forcefully and silently while promoting the belief that it would be biologically impossible for an intersex person to have ever been born. That many people today have never heard of an intersex person and have no idea that such a person could exist is far from inevitable. It is, in fact, the result of a specific series of historical events that many of us are never taught, because if we knew about them, it would make the societal and surgical attempts to erase intersex people much harder to ignore.

The surgical model and its ugly roots

The belief that human sex is a strict, biological binary and human gender is a natural, binary extension of a body’s sex (aka the sex/gender binary) is not an ancient, evolutionary truth but a modern myth. According to this myth, sex and gender are expected to always align as either man/male or woman/female. This belief emerged in the 1800s from a combination of disruptive scientific discoveries, anxieties about race and power, and the developing eugenics movement.

The discovery of gonads, testes and ovaries, triggered a shift from the previously dominant understanding of all human bodies as variations of one type to the perception of male and female bodies as distinct types distinguished by their gonads. Meanwhile, Charles Darwin first published his theory of evolution in 1859, which presented a serious challenge to polygeny, a form of scientific racism which argued that different racial and ethnic groups of humans had entirely separate evolutionary ancestry. Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices aiming to selectively alter and “improve” the genetics of human populations, was also growing in popularity in the late 1800s in both the US and Europe. Following the discovery of gonads and the introduction of Darwin’s evolutionary theory, practitioners of eugenics appropriated and twisted both together to lay the groundwork for the future of intersex surgeries.

As old racist arguments in support of polygeny declined in popularity, these eugenicists warped together the recent scientific discoveries of gonads and evolution to create a new type of scientific racism that asserted that the most superior and most ‘evolved’ individuals were heterosexual Europeans. They claimed this superiority was shown by the supposedly greater differences (referred to as sexual dimorphism) between the bodies of heterosexual, European men and women in comparison to non-European, non-heterosexual people. As a result, both actual intersex people and those with bodies these eugenicists perceived as not being sexually dimorphic enough (deemed not “manly” or “womanly” enough) were seen as inferior.

Eugenic projects are dependent on increasing the reproduction of individuals that the eugenicists believe to have “superior” traits. Intersex people were not only seen as supposedly inferior to heterosexual, dimorphic Europeans but also a threat to maximizing heterosexual reproduction to further white supremacy (as intersex people were assumed to be less fertile, non-heterosexual, and capable of “corrupting” others) and create more sexually dimorphic people.

Although these eugenic perspectives are less explicitly stated today, dominant cultural beliefs about sex and gender remain connected to race and racial stereotypes. One of the ways we see the link between racism and intersexism is in athletics: it is usually non-white women (intersex or not) who are perceived as “not feminine enough” and targeted for harassment and sex testing.

Enforcing binary sex, gender, and heterosexuality

These ideas about sex and gender, race, and social hierarchies laid the groundwork for the OGR model once the scientific tools for surgeries and hormonal alterations on intersex people became available. However, doing surgeries to reduce the appearance of sex trait variations was not enough to cement the sex/gender binary, because the existence of intersex people (and therefore the supposed “necessity” of these surgeries) disproved any biological argument for a human sex binary.

Cultural anxieties about intersex people’s sex and gender already existed, and the OGR model further stressed the belief that a child with sex trait variations could not possibly grow up to be a well-adjusted adult. Doctors following the model also claimed that the child’s family, community, and potential future partners could not possibly accept someone with such physical differences. By framing the birth of an intersex child as a social emergency, the clinicians promoting the OGR model made it appear as if their recommended ‘normalizing’ procedures and concealment of children’s intersex status were the only possible option.

The OGR model was never just about changing the physical appearance of an intersex child’s body. This approach to intersex medicine has always been about enforcing the cultural norm of a sex/gender binary in which only dimorphic and heterosexual men and women could exist. Under the OGR model, surgical decisions were often made based on what role in heterosexual intercourse the surgeon thought the infant could best fulfill in the future. This assessment of possible surgical outcomes, according to the model, determines the gender of a child. Doctors and parents are then expected to teach that child to believe this is the gender and body they have always had.

The mythical tale of the sex binary

The OGR model depends on the mythology of an intersex future that will never happen, an intersex past that has never existed, and a social and scientific story of binary sex that persists, despite being biologically inaccurate. This mythology also reinforces itself: the stronger the belief that intersex people do not exist, the stronger the motivation to make intersex children into “formerly-intersex adults” (because how can a child be allowed to grow up into something impossible?) Over time, the idea of intersex futures becomes more and more of an impossibility.

Non-consensual surgeries are not the only strategy used to suppress the possibility of intersex futures. For the many intersex people like myself who don’t develop or discover that we have sex trait variations until puberty or later in life, we are prevented from expressing our intersex traits through coercive medical care, social stigma, and internalized exorsexism. We may be denied access to accurate assessments and imaging, pressured to undergo surgeries and take exogenous hormones, spend endless time and money on hair removal, face rejection and harassment, internalize profound beliefs of our brokenness and otherness, the list goes on.

The harm and stigma we experience from coercion or neglect at the hands of the medical system is coupled with the harm and stigma of living in a cultural sex/gender binary in which our bodies are mocked, demonized, or erased.

The fear of becoming what I always had been

When I was a child, before I knew I was intersex, the only portrayals I ever saw of people like what I am now were as circus acts, seen as “freaks” for their unusual biology, or as jokes and parodies of culturally unimaginable gendered failure. Such a future felt unthinkable, and I believed I would have to spend the rest of my life doing everything I could to avoid allowing it to become my reality.

When I was 18 and went to college, I didn’t yet have a name for what was happening to me, and had privately adopted the supernatural belief that I had, in this life or a past one, done something unthinkably awful to have brought upon myself a body that none of the puberty books I’d read had said was possible.

When I was 22 and started graduate school, I had just received a diagnosis and was consumed with the daily work, pain, and endless self-surveillance required to enact a normalized, gender passing body.

When I was 26, scared and uncertain and very unconvinced, I decided to see what would happen if I tried something else.

I am incredibly grateful for the knowledge, community, and support that made it possible for me to contemplate and eventually embrace existing as an openly and visibly intersex person. I also now understand that all of these versions of me, at 18, 22, 26, and beyond, were already living an intersex future. There has been no time in my adult life that I have not been grappling with the physical and psychological consequences of being born into an extraordinary body and how I have decided to live with it.

Author Sam Sharpe

In spite of the OGR model, the coercion, and the deep, deep, deep shame, intersex futures are not only possible, but inevitable. Intersex scholar Cary Gabriel Costello writes

An important point intersex people…make about the medical impulse to normalize bodies to the sex/gender binary is that, in the end, normalization is not in fact possible. First, medical interventions may reduce visible sex-variance, but only to a degree… And even if an individual’s body appears to conform to sex-binary ideals, birth status persists forever.

Intersex futures can never be erased

The 1996 protest which is now commemorated yearly as Intersex Awareness Day, as well as the pre-existing and ongoing work of the intersex rights movement, are a refusal of the myth that intersex futures are impossible. Beck and Holmes’ presence at this protest as intersex adults was living proof of Dr. Costello’s assertion that, despite the profound harm, attempted erasure, and medical violations, intersex bodies cannot be “normalized” out of existence and intersex adults will always exist.

What does not yet exist, and what intersex people and our allies continue to demand, is intersex liberation. This must include the ability for intersex children to grow up into intersex adults in the bodies they were born with and the full knowledge of their own natural histories.

What I want in an intersex future is not just the absence of nonconsensual surgeries, coercive hormone prescriptions, and categorical erasure. I’ve written before about my apprehension with the concept of ‘awareness’ and awareness days. But when I let myself imagine a future in which my intersex body is seen as possible, it also includes a collective, commonplace, and elemental understanding that intersex people exist.

It means understanding that even if you have never knowingly met an intersex person, that we are here, in every place and time that humans have existed, doing the same remarkable and unremarkable things as everyone else. It means parents knowing that, if they have children one day, those children might be intersex. It means going on a first date and knowing that your date might be an intersex person. It means the awareness that, whether you know it or not, some of the people you love and work with and pass on the street will be intersex.

Having turned 32 this year, I’m older than Intersex Awareness Day, but still young at being openly intersex. In just the last few years, I’ve chosen to exchange the work and shame of trying to hide this part of myself for the unique joys and unpredictable consequences of being visibly sex variant, moving through the world in what I know many still consider to be an impossible body. I’ve been harassed, rejected, misunderstood, pathologized and more.

But I no longer feel fractured and ashamed by the inevitability of my intersex future, by this birth status that persists forever. And, to me, that is worth it.