Are people with MRKH—with mostly typical sex anatomy but born without a uterus and/or parts of the vagina—considered intersex? To get anywhere, we need to be asking completely different questions.

By Maddie Rose

As a teen newly navigating dating and sexuality, I received news that turned my world upside-down: a diagnosis of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, or MRKH. I was born with no vaginal canal or uterus. I don’t have periods, but I do have ovaries that give me otherwise typical hormonal cycles. Most people with MRKH are raised as girls and are not diagnosed until their teen years when menstruation never begins.

So, are we intersex? Nobody can seem to agree.

When I first tried to find community, I found myself in MRKH support groups advertised as being for women and girls with my condition. Most posts started out with a friendly “Hey ladies!” I didn’t love these greetings, but I understood why those groups focused so heavily on womanhood. Our society suggests women are only “real women” if they can have penetrative sex to fulfill men’s sexual needs, and can carry and birth babies in their own uterus. This results in many people feeling put on the defensive about being “enough” of a woman. Group members shared heartbreaking stories of doctors, boyfriends and parents reacting negatively to our differences, especially infertility. They often avoided any language they thought could contradict womanhood—like “intersex.”

But what I’ve learned is, intersex doesn’t mean “not woman.”

Is MRKH considered an intersex condition?

Many years after my experiences in MRKH support groups targeted to women, I stumbled on the term “intersex” for the first time. I saw it used for many people who, like me, had unique and complex experiences around bodies, doctors, fertility and sex.

So, is MRKH considered intersex? Defining intersex is tricky. Many people imagine the term intersex to mean someone born cleanly between typical “male” or “female” sex characteristics, or with a mix of both. However, many of these tight definitions were shaped by advocates whose bodies had more “mixed” sex characteristics. Other people, like those I knew with MRKH whose bodies developed closer to the “typical female” path, tended to prefer medical language like “having a disorder of female sex development.” They often embraced these tight definitions of intersex specifically because they were excluded from them. As a teen, this confused me—isn’t a variation in sex development exactly what intersex is?

I found support groups of intersex people from all different medical backgrounds with similar experiences to me. We built a shared culture of positivity around our bodies.

The women in the MRKH support groups I belonged to prioritized medical changes to fit into a physical idea of womanhood. Many people pursued ways to have penetrative sex, either through vaginal dilation or surgery, and closely followed scientific developments in uterine transplants. These are all completely valid paths, they just aren’t the only paths.

People who prefer the word “intersex” may also want surgery, and many intersex people are women who want to affirm their bodies through medical changes. What struck me was that the language I heard in MRKH groups about surgery as a necessity in order to have sex was very different than the language I later heard in intersex circles.

In intersex groups I had more conversations with people who could relate to my bodily experiences with humor instead of shame—like laughing along at my habit of regularly ordering takeout to fulfill my emotional cravings because, who knows, I might actually be on my period right now. (A little MRKH joke for those without a uterus.)

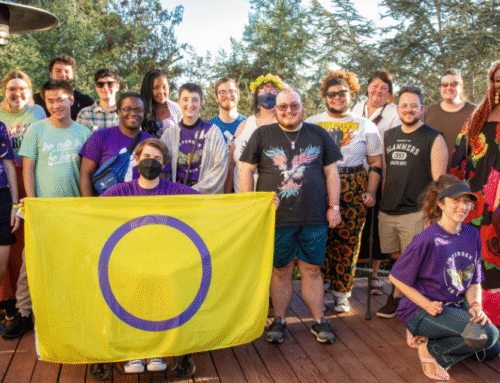

I found support groups of intersex people from all different medical backgrounds with similar experiences to me. We built a shared culture of positivity around our bodies. There was no suggestion that medical treatments were the only way to have sex, to be a parent, or to feel comfortable in your own skin. Together, we united around the belief that we were part of human diversity, instead of conditions in need of fixing. I found many of those people here at interACT!

MRKH + Gender = ?

Exploring my gender on my own terms was different than feeling like a “broken woman” in a medical sense. I felt free.

The MRKH Facebook groups I found only talked about being “enough of a woman,” which stunted me from understanding that I am transgender and nonbinary. I’m not either of those things because I am intersex or have MRKH. But my MRKH experiences gave me an opportunity to seriously think about my gender and what being a woman meant to me. The answer in the end was, “nothing, really.” But that’s different for everyone. Among a broader intersex community, I realized that people with variations in their sex anatomy identify themselves in so many ways: cisgender, transgender, men, women, nonbinary, and more.

Having MRKH never made me “less of a woman.” Many people with MRKH are happy to live their lives as women and have never felt otherwise. But I didn’t really want to be a woman, nor did I feel like one. The intersex community helped me to understand my own gender, and to understand the gender restrictions placed on me by society. Exploring my gender on my own terms was different than feeling like a “broken woman” in a medical sense. I felt free.

Who counts as intersex?

A female friend born with internal testes once told me, “I guess I’m technically intersex, but I don’t care or call myself that. I’m just a cisgender woman who has testes.” This just goes to show that ideas about who falls into “intersex” vary widely. Perhaps the real question is not “who counts as intersex” but: how can we all be free from harmful expectations on our bodies, and what kind of community do we need to build to achieve that world?

Intersex spectrum people often share overlapping struggles around medical trauma, sex and intimacy, hormones and surgery, body image, and connections between their bodies and gender identities.

I don’t believe that shame, limited physical definitions of womanhood, or “fixing” will get us there. We need a wider, more inclusive intersex community that includes everyone with some kind of shared experience in reclaiming agency over their unique sex development.

A broader understanding of “intersex” benefits not only MRKH folks on the supposed margins of “intersex”—but everyone! Breaking down expectations of bodies breaks down shame. As transgender advocates say, genitals do not equal gender. Likewise, cisgender women who discover they are infertile, or cisgender men who worry about their genital size, can feel relief when their genders are not seen as dependent on their bodies.

I want to see intersex as a spectrum and umbrella label. Intersex spectrum people often share overlapping struggles around medical trauma, sex and intimacy, hormones and surgery, body image, and connections between their bodies and gender identities. And almost all of the conversations I saw in MRKH women’s spaces dealt with these themes exactly.

Labels are entry points into worlds of support and shared experience. Having a term attached to a pattern of experiences, like “intersex,” can provide people with pride and love for their bodies that were otherwise shamed, medicalized, and hidden away. Those communities can also exist as spaces for advocacy and activism, leading to acceptance and freedom. We all deserve that.

This piece is part of the Intersex Awareness Day 2020 series on intersex health and resilience.