Sam Sharpe hugs fellow athletes at a swim meet

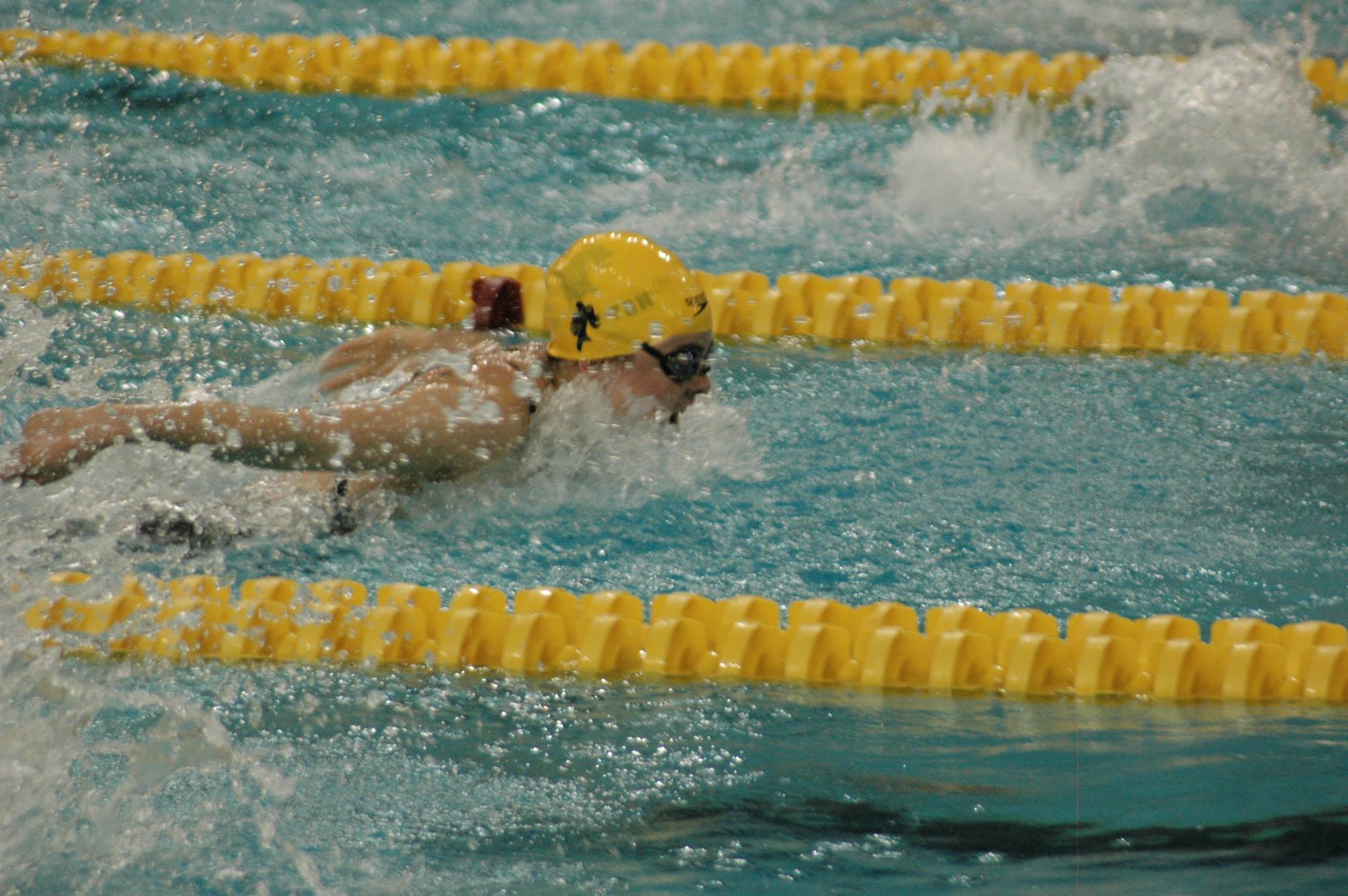

211 is a number I think about often. Two minutes, eleven seconds was the time it took me to swim the 200 Yard Butterfly during the finals of the 2014 Minnesota Intercollegiate Athletic Confrence’s Swimming and Diving Championships, my last college swim meet and one of the happiest nights of my life. I had broken my personal record by two seconds, the fastest I had ever swam as an NCAA D3 swimmer. And while I knew at the time that I was different from most of my fellow athletes, I didn’t yet realize it was because I was intersex, and fortunately neither my college nor my athletic conference ever challenged my ability to compete because of it.

Almost a decade later, I continue to cherish the profound joy and accomplishment I felt in the pool that night, as well as the many happy and meaningful memories from the 8 years I spent training and competing as a varsity swimmer in high school and college. Through these experiences, I learned to set goals and push past my limits to accomplish them, and also found a deep sense of community, belonging, and friendship with my teammates.

Learning why I was different

While I shared with the rest of the team a commitment to improving our times and supporting each other through difficult practices, I was also aware that something was different about me from the other swimmers, but I didn’t know exactly why. When I was younger, I had been teased and bullied for looking different, and it was a huge relief that my college teammates cared more about what we had in common and accepted me as just another swimmer.

In my 20s, after seeing multiple doctors and receiving a variety of assessments including blood work and imaging, I eventually learned that I have an endocrine condition that results in naturally occurring sex hormones that do not match up with either the typical male or female ranges. I am intersex, which is an umbrella term for individuals who are born with physical traits which do not fully align with male or female sex categories.

I could be disqualified from athletics today

If I was competing in high school or college athletics today, I would have much more to worry about than just being teased for looking different than other athletes. As of June 2023, 22 states have banned transgender students from playing on the team that aligns with their gender identity in K-12 athletics and in some cases NCAA athletics as well. While these bans directly target transgender student athletes, they also have a profound impact on intersex athletes like me.

Even though intersex people like me exist and are not uncommon, arguments for the exclusion of transgender athletes from athletic teams that match their gender identity are based on the assumption that all human bodies conform to a distinct male/female sex binary. In reality, human sex consists of 7 main traits (sex chromosomes, gonads, external structures, internal structures, sex hormones, sex hormone response, and secondary sex traits) which all have many different possible variations.

Just like there are more than two possible eye colors or two possible hair colors that people can be born with, there are far more than two possible combinations of sex traits in human populations. An estimated 1.7% of the population has a combination of these 7 traits which distinctly differ from the male/female binary. This percentage increases to 5% or more if additional variations of sex hormones and secondary sex traits are included. Because there is so much variety in which sex traits different people are born with, laws that create narrow expectations for what types of bodies male and female athletes need to have don’t work.

If I was competing in high school or college athletics today, I would have much more to worry about than just being teased for looking different than other athletes.

If I was competing in high school or college athletics today, I would have much more to worry about than just being teased for looking different than other athletes.

Many trans sports bans use language similar to Kansas House Bill 2238, which passed in April and defines biological sex as “the biological indication of male and female in the context of reproductive potential or capacity, such as sex chromosomes, naturally occurring sex hormones, gonads and nonambiguous internal and external genitalia present at birth.”

Definitions like these attempt to erase intersex people from existence and seek to exclude us from playing sports because of the sex trait variations that we were born with. Many intersex people have bodies that don’t fit into the definitions of male or female outlined in these laws, and there is no explanation for what team an intersex athlete can play on, threatening to exclude us entirely from athletics.

Sam swims at a meet

Exclusion and scrutiny of intersex athletes is nothing new

Many trans people and allies who have advocated against these types of bills are not aware of the ways that they also impact intersex individuals. However, any legal, medical, or visual assessments that attempt to determine which students are trans and prevent them from playing on sports teams that align with their gender will also lead to scrutiny and potential exclusion of intersex students.

Since the 1960s, elite women athletes have been subject to a variety of humiliating and traumatic procedures, including mandatory genital exams and invasive medical testing, in an unsuccessful attempt by athletic governing bodies to verify each athlete’s “biological femaleness.” These sex verification procedures have traumatized and disqualified many intersex women athletes, including those who had no previous awareness of their intersex status. Such procedures are incompatible with creating a fair, inclusive, and supportive environment for athletes, especially children and teenagers.

Trans sports bans serve to extend these types of scrutiny and discrimination from elite sports into K-12 and collegiate athletics, and will result in intense scrutiny of the bodies of all student athletes, invasive physical examinations, and/or mandated disclosure of personal medical information, likely leading to an overall decrease in participation.

These sex verification procedures have traumatized and disqualified many intersex women athletes.

These sex verification procedures have traumatized and disqualified many intersex women athletes.

Intersex and trans athletes are not the threat. We are under threat.

In the years since I swam my last college race, I have continued to face discrimination, harassment, and threats to my civil rights because of the way that I look and the fact that I am intersex. The perseverance, determination, and resilience I learned as an athlete continue to enable me to withstand and advocate against these forms of antagonism. I will always be grateful for these skills and the experience of being able to train and compete with my team without facing regulatory scrutiny and possible disqualification as a result of my physical differences.

Intersex and transgender athletes do not threaten fairness or safety in women’s athletics, but trans sports bans imposing invasive examinations of athletes’ bodies, appearances, and medical records absolutely will.

These insidious and ongoing attacks on trans and intersex athletes are one of the many reasons why we need #TransIntersexSolidarity in our shared fight to preserve our rights, safety, and autonomy.

Sam in a Little Apple Pride shirt