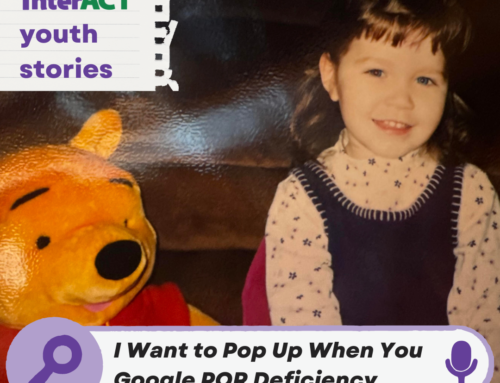

Liat Feller, age 3

INTRODUCTION

I always knew I was queer, and I’ve been “out” since I was sixteen, but I didn’t know that I was intersex until my early twenties.

My first intersex traits appeared as early as age eight. By thirteen, I was well accustomed to invasive exams, procedures, and hormone therapies that lacked informed consent and are all too common an experience for intersex youth. Doctors had led me to believe that my assigned-female body was broken, sick. I could be cured, finally a “normal girl,” if only I could rid my body of its facial hair and masculine-leaning build.

Fast forward to pandemic-times, after discovering the truth about my medical care and going through a whole bunch of therapy, I made the nerve-wracking, but affirming, decision to stop all medical interventions that sought to change my sex characteristics. I stopped the diets, the hormones, the heavy makeup and caustic hair removal that had become a too-big part of my routine.

Around the same time, I began connecting online with other intersex people, with my variations and other variations. What I learned is that the doctors were wrong – I could never be cured. This wasn’t for a lack of a cure, but rather because I wasn’t broken – I wasn’t sick – in the first place.

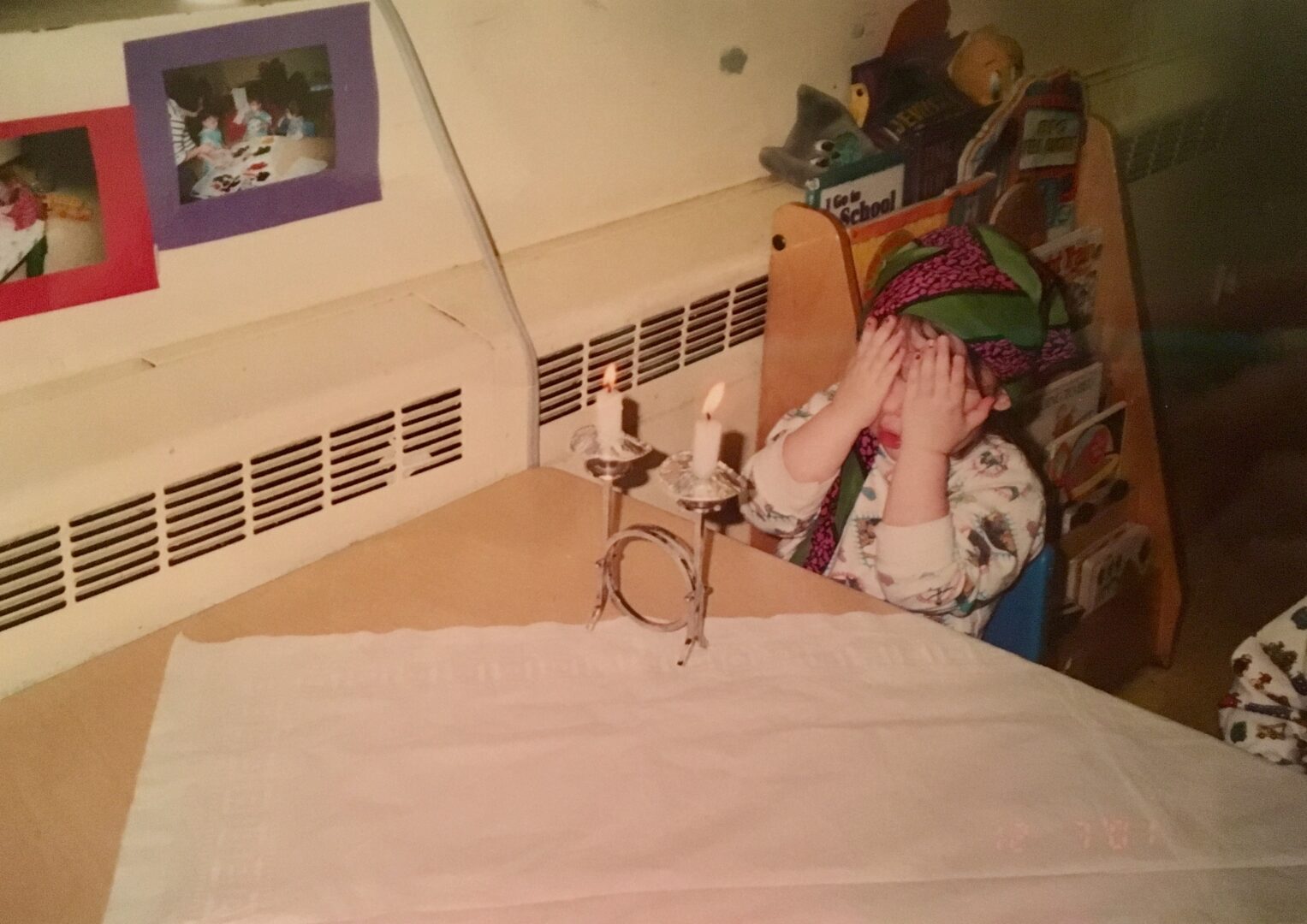

When I came out as intersex, I was fortunate to be surrounded by a decent number of friends and family who were happy for me, even if they didn’t totally understand the whole intersex thing. My bigger struggle was when it came to the spiritual. I was raised with a strong Jewish identity, and a deep love of yiddishkeit (the word used by many Jewish communities to describe the essence of our traditions, culture, stories, and way of being). I’d resolved that my eventual marriage to not-a-man might present a challenge to a by-the-book Jewish wedding, but I’d cross that bridge when I got to it.

Now that I was visibly gender-non-conforming and could no longer pass as cisgender or endosex, I struggled to understand my place in my traditionally gender segregated Jewish community. I knew I didn’t belong on the men’s side but I was super aware that I wasn’t welcome on the women’s side either. I found myself straddling a metaphorical, and sometimes literal, mechitza (the divider between the men’s and women’s sections in traditional Jewish prayer spaces).

These experiences, some affirming, some painful, inspired me to go back to where it all began – the ancient Jewish texts. What did my ancestors say about intersex people or people who defied the boundaries of gender? There are ten times as many intersex people in the world (at least ~2%) as there are Jewish people (0.2%) so I figured the Rabbis had to have something to say.

The days between Intersex Awareness Day (October 26th) and Intersex Day of Remembrance (November 8) remind me of the Days of Awe between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; a time of introspection, prayer, mitzvot (good deeds) and manifestation for the year ahead. This intersex holiday season, as I like to call it, gets me thinking a lot about my inner child. As a preschooler, I remember learning the golden rule from Vayikra (Leviticus) 1:27: love your neighbor as yourself, or as I fondly remember singing with my friends each day during circle time:

“V’ahavta l’reacha kamocha (English: And love your fellow as yourself)

zeh klal gadol baTorah… (English: That’s the greatest principle in the Torah)

Don’t walk beside me, I may not follow.

Don’t walk behind me, I may not lead.

Just walk beside me and be my friend

and together we will walk in the ways of Hashem.”

No person inherently more or less precious than their fellow, walking in the “ways of Hashem (G-d*)” means treating every human – friend or not, alike you or not – with love, respect, and dignity. Walking “together,” beside one another, means being an ally. So why wasn’t I feeling this consistently from the community that raised me? I explored Jewish texts, new and old, and what I learned blew me away.

As Jewish communities across the globe call for solidarity against Antisemitism, Islamophobia, and other forms of hate and injustice, it’s more clear to me than ever that the vision for true peace can only be realized if it is a common goal. We can only create a better, peaceful, more just world, if we truly walk beside one another, not despite our differences, but in light of them.

This intersex holiday season, my first season fully “out,” I’m sharing with the world a piece of my Jewish intersex story and my Jewish intersex heart. I invite you to open your mind and open your heart. My hope is that you’ll take with you an expanded understanding of the intersex community, what it means to be an intersex ally, what it means to embody Jewish ethics, and perhaps above all – what it means to love your fellow human.

AN INTERSEX 101

Here are some basic definitions which are by no means comprehensive. They are intended to establish a common understanding of some terms used throughout this guide and frequently used when discussing topics related to gender, sex, and intersexuality.

Gender – behavioral, cultural, and psychological traits typically associated with the terms man/male, woman/female or nonbinary

Sex – assigned (sometimes incorrectly) at birth usually based upon phenotypic traits

Male – XY, scrotum, penis, and testicles, testosterone-dominant traits

Female – XX, vulva, vagina, clitoris, ovaries, and uterus, estrogen-dominant traits

Intersex – born with sex traits (primary or secondary; visible or invisible) that vary from the above narrow definitions of male or female

Endosex – not intersex; having a sex categorization of male or female

Intersex is an umbrella term for variations in sex traits or reproductive anatomy. Intersex people are born with these variations which may manifest at birth, in childhood or even later in life. There are many possible variations in genitalia, hormones, internal anatomy, or chromosomes, compared to the usual two ways that human bodies develop. An intersex person has variations in one or more of these areas.

Some intersex traits are noticed at birth. Others don’t show up until puberty or later in life. Intersex people often face shame—or are forced or coerced into changing their bodies, usually at a very young age. This can include surgery, often in infancy or early childhood, and other medical treatments. Contrary to what some people in my life would like to believe, there is no ICD-10 code, no doctor or overseeing body who one day crowns you “intersex enough.” There are over 40 biological variations which can be considered intersex.

Intersex people come from all socioeconomic backgrounds, races, ethnicities, genders and orientations, faiths, and political ideologies. Our intersex community is united by our experiences living with natural variations in our sex traits and our journeys toward bodily integrity and autonomy.

So, what do Jewish texts say about the sex and gender binaries?

THE ORIGINS OF (INTER)SEX

In order to understand what the classical Jewish texts say about intersex and social justice, we must first understand how the classical Rabbinical frameworks of sex and gender compare to our present-day understanding of the concepts. The classic Rabbis did not understand sex and gender to be separate phenomenons, but rather understood a single concept best described using today’s language as gender-sex. That’s not to say it was at all binary though. While it’s true that the classical Jewish texts understood gender-sex to exist within a binary axis, they understood very well that not everyone fit into these categories or within the axis at all. We begin…

The Eight Gender-Sexes Recognized by Classical Jewish Texts

Adapted from a variety of sources including Rabbi Elliot Kukla, Abby Stein, Rachel Sheinerman, and Shoshana Fendel

- Zachar, male.

- Nekevah, female.

- Androgynos, having both male and female characteristics.

- Tumtum, a person whose gender-sex is unclear or obscured.

- Aylonit hamah, identified female at birth but later naturally developing male characteristics.

- Aylonit adam, identified female at birth but later developing male characteristics through human intervention.

- Saris hamah, identified male at birth but later naturally developing female characteristics.

- Saris adam, identified male at birth and later developing female characteristics through human intervention.

There are over 400 mentions throughout Jewish classical texts of gender-sexes that align with our definitions of intersex and transgender.

Nothing New Under the Sun

| Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) 1:9-10

(9) Only that shall happen which has happened, only that occur which has occurred; there is nothing new beneath the sun! (10) Sometimes there is a phenomenon of which they say, “Look, this one is new!”—it occurred long since, in ages that went by before us. |

קהלת א׳:ט׳-י׳

(ט) מַה־שֶּֽׁהָיָה֙ ה֣וּא שֶׁיִּהְיֶ֔ה וּמַה־שֶּׁנַּֽעֲשָׂ֔ה ה֖וּא שֶׁיֵּעָשֶׂ֑ה וְאֵ֥ין כּל־חָדָ֖שׁ תַּ֥חַת הַשָּֽׁמֶשׁ׃ (י) יֵ֥שׁ דָּבָ֛ר שֶׁיֹּאמַ֥ר רְאֵה־זֶ֖ה חָדָ֣שׁ ה֑וּא כְּבָר֙ הָיָ֣ה לְעֹֽלָמִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר הָיָ֖ה מִלְּפָנֵֽנוּ׃ |

Like the passage says: there’s nothing new beneath the sun. This is one of my favorite adages from Jewish texts. Every concept, every phenomenon, every feature of our lives – has existed, explicitly or not, in a past iteration. Despite what some people want to believe, intersex people aren’t new. We’re well documented in history, memoirs, art, and as you’ll read below – classical Jewish texts.

In his book, Trans Talmud, Max K. Strassfield expands upon how the very fact that the Rabbis sought to “define what makes [androgynos] and [tumtumim] unique” demonstrates the historical existence and significance of bodies outside the popularized male/female binary. He says these efforts “point to the changeability of bodies and to the way all bodies may refuse to develop in accordance with normative gendered expectations.”

Intersex – that is, non-endosex – bodies have always been here. Not just that, but Judaism knows it and shows it loudly and proudly.

IN THE VERY BEGINNING

| Bereshit (Genesis) 1:27

(27) And G-d created humankind in his own image, in the image of G-d, G-d created it; male and female G-d created them. |

בראשית א׳:כ״ז

וַיִּבְרָ֨א אֱלֹקים ׀ אֶת־הָֽאָדָם֙ בְּצַלְמ֔וֹ בְּצֶ֥לֶם אֱלֹקים בָּרָ֣א אֹת֑וֹ זָכָ֥ר וּנְקֵבָ֖ה בָּרָ֥א אֹתָֽם׃ |

Just like in English, in biblical and modern Hebrew language, nouns, adjectives, and genders must agree in plurality (or lack thereof). Genesis 1:27 utilizes both singular and plural direct object forms to describe humankind. Nothing in the writing of the Torah is by accident – it all has meaning – so the Rabbis asked, why the mismatch?

COMMENTARIES

Midrash (classical Rabbinical commentary on the Torah) – 6th Century, Roman-Controlled Palestine

And G-d said: Let us make Adam in our image, in our shape: R’ Yirmiyah ben Elazar said, when Hashem created Adam HaRishon, he was created as both genders; thus is it written, “male and female [he created them].”

The Midrash is among the earliest commentaries on the Torah. As the Jewish people were forced to spread amongst the diaspora, the oral commentaries on the Torah were recorded in writing, lest they be lost in the exile and chaos of the time.

Rabbi Yirmiyah ben Elazar explains in this midrash that the mention of humanity with the singular it and then subsequently referring to the plural male and female them is because Adam HaRishon (the first human) the first human to be had a collection of male and female traits – essentially, they were intersex. This is one of the earliest known recorded uses of the singular they, and in addition to proving the always-existence of intersex people, show us that if G-d used the singular they, it must be grammatically correct (but that’s an argument for a different guide).

Mishna (a.k.a. Oral Torah – a compilation of Jewish traditions) – 2nd Century, Roman-Controlled Palestine

An Androginus (a hermaphrodite, who has both male and female reproductive organs) is similar to men in some ways and to women in other ways, in some ways to both and in some ways to neither.

As early as the second century, Rabbis – who were consulted on religious but also ethical and medical issues – knew that an intersex person might have characteristics of a binary sex, but they are also a category unto themselves. In other words, the ancient Rabbis knew that an intersex person wasn’t just a “defective” male or female. Sounds like a pretty modern take, right? Well, it’s among the oldest documented perspectives on intersex in the whole world.

Before I move on to another piece of commentary, a bit of context on the Mishna’s use of the h-word: Ancient commentaries use hermaphrodite instead of intersex because this was the language available at the time to describe people with mixed sex characteristics. Hermaphroditus (the h-word’s namesake) was a Greek mythological character who had complete sets of both male and female genitalia. To have two complete sets of genitalia is not biologically possible; you cannot have “both.” This common mis-definition of intersex, among other persecution, erasure, and discrimination, contributed to hermaphrodite becoming a slur used against intersex people. Today, some intersex people have reclaimed use of the word (evocative of reclamation of the word queer) but use outside of historical and intersex-led contexts should be avoided.

Rabbi Margaret Moers Wenig, D.D., Senior Lecturer in Liturgy and Homiletics at Hebrew Union College

Read not “G-d created every single human being as either male or female.” This verse is… a merism, a common Biblical figure of speech in which a whole is alluded to by some of its parts. When the Biblical text says, “there was evening, there was morning, the first day,” it means, of course, that there was evening, there was dawn, there was morning, there was noon time, there was afternoon, there was dusk in the first day. “Evening and morning” are used to encompass all the times of day, all the qualities of light that would be found over the course of one day.

So, too, in the case of this verse, the whole diverse panoply of genders and gender identities is encompassed by only two words, “male” and “female.” Read not, therefore, “G-d created every kind of human being as either male or female” but rather “G-d created humankind male and female and every combination in between.”

Rashi – 11th Century, Northern France

IN THE IMAGE OF G-D HE CREATED HIM — It explains to you that the form prepared for him was the form of the image of his Creator.

According to Jewish tradition, we are each made b’tzelem elokim – in the image of G-d. That means that G-d themself contains multitudes. G-d contains the essence of all of us at the same time – every sex, every gender, every race, ethnicity, ability, every walk of life. G-d created the world, and each of us, with intention.

Depending on your own spiritual understanding, G-d might be a concrete omnipotent being somewhere in the great beyond, or they might be the intangible essential chance that allowed millenia of science and evolution to create humanity as it is today. Whatever your understanding of a higher power, or lack thereof, the essence is still the same: you are natural, you are divine, and you are meant to be.

Rabbi Elliot Kukla, 2007, Reform Devises Sex-Change Blessings

The Midrash . . . adds that the [first human] being formed in G-d’s likeness, was an androgynous, an inter-sexed person . . . Hence, our tradition teaches that all bodies and genders are created in G-d’s image, whether we identify as men, women, intersex, or something else.

HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS

If Judaism is inherently queer-affirming, how come it didn’t stay that way across denominations?

The short answer: Centuries and centuries of colonization, white euro-centrism, queer-erasure, and antisemitism along with and followed by centuries of fear of assimilation led to inter-denominational schisms and exacerbated intersex erasure.

The long (but still incomplete) answer: Understanding of human sex development has varied through millennia. In one of the earliest accepted records (read: records accepted by the general public/from sources other than indigenous cultures whose concepts and validity were never acknowledged), Artistotle describes females as “incomplete” males, lacking a high internal body temperature which he believed induced characteristically male traits.

In the context of the Doctrine of Discovery, around the time that the Church became the Catholic Church, a papal bull (decree) forbade, in the name of Christianity, practice of any gender and sex theory outside the male/female binary.** This included the Jewish tumtum and androgynos as well as gender-sexes in plenty of indigenous cultures, some of which were entirely wiped out.

For groups who weren’t wiped out, staunch enforcement of a sex-gender binary by the Church meant discrimination and historical erasure of people who existed outside the binary. In order to survive, recognition of nonbinary sex and gender identities fell out of favor. Intersex is natural, humans are resilient, and the arc of history bends towards justice. Intersex people continued to exist, and continued to be erased, and continued to exist, and continued to be erased, and so on.

THE MODERN SEX BINARY

How do modern and contemporary medicine view intersex bodies?

When a baby is born, an M or F box is checked on the birth certificate and the child is assigned male or female. Everyone cheers, “it’s a boy” or “it’s a girl,” even though science knows gender ≠ sex, and that sex is not binary. A vagina and vulva – female raised as a girl; scrotum and penis – male raised as a boy.

When an intersex child is born, they may or may not have visible intersex traits. Some traits like internal testes or Mullerian agenesis are only visible with medical scans and other traits like hyperandrogenism don’t become evident until later in life. Infants with intersex traits visible at birth don’t always get the “it’s a boy/girl/baby!” cheer with which babies who appear endosex are welcomed into the world.

Medical teams usually don’t even say the word intersex. They tell the new parents that their child has a “Disorder/Difference of Sexual Development***” (DSD) and may present a plan to surgically and/or hormonally mold the deemed-defective male or female as close to typical as possible. The tide is changing, slowly, to embrace a greater value of bodily autonomy. Still, it’s not a typical practice to assign anyone ‘intersex’ at birth. Whether because of unnecessary surgery and forced assignment, picking a category that seems the closest to the infant’s perceived sex traits, or because the doctors just didn’t know, most intersex individuals are assigned male or female at or shortly after birth.

INTERSEX RIGHTS TODAY

What do intersex rights look like today?

Historically, medical professionals have advised parents of intersex children to keep their variation a secret, often even from the child themself. A young intersex person may or may not know why they are at the doctor so frequently or why they have certain experiences so different from their peers. Intersex people who learn about their variation during puberty or later in life may or may not be told that their condition is an intersex variation. They’re given the same advice – don’t tell – and sometimes find that their variation was described in earlier medical records that were hidden from them or destroyed.

Medical, social, and political environments raise an intersex person to be ashamed of their body and isolated from peers with similar experiences. By the time they are an adult, many intersex people have experienced physical and psychological trauma in the form of incompetent healthcare, coerced surgical and/or hormonal interventions, a lack of representation in school and the media, and a lack of community. We generally feel isolated, alone, and “othered” – even in places that call themselves LGBTQIA+ inclusive.

Thanks to a fierce and resilient community of intersex rights activists (and allies), attitudes and the medical tide are changing, albeit slowly. No hospital in the United States has a comprehensive policy against medically unnecessary intersex surgeries and procedures. After a lengthy battle spearheaded by the Intersex Justice Project, Lurie Children’s hospital ceased performing some intersex surgeries; as of this writing, they still perform others everyday.

The United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association have all condemned intersex genital surgeries as a human rights violation and NYC Health and Hospitals has a policy to defer cosmetic pediatric intersex surgeries. Hospitals and medical systems across the country continue to perform unnecessary surgical and medical interventions on us everyday. Intersex activist, author, and Human Rights Commissioner for the city of Austin, TX Alicia Roth Weigel collaborated with Kind Clinic to open the first adult intersex healthcare clinic nationwide, and the first to be created from the ground up with the guidance of intersex people.

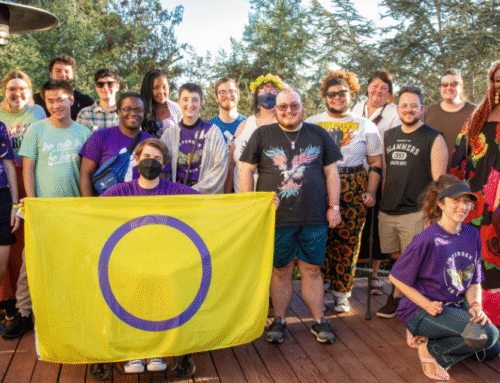

Organizations like interACT, Intersex Justice Project, and InterConnect (plus many more nationally and internationally) fight for intersex awareness, solidarity, community, and rights every single day.

INTERSEX RIGHTS TODAY: A CALL FOR SOLIDARITY

On Lived Experience

What do classical Jewish texts say about social justice and how can that steer intersex activism and allyship today?

What I consider to be most beautiful about Jewish ethics is that they do not guide us by dictating our actions. They seldom tell us exactly what to do. Each case, each context, and each Jew is as unique as there are stars in the sky, grains in the sand, or particles of dust in the atmosphere. Classic Jewish texts and the teachings of Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism) teach us that we are holy as holy can be, with great potential and responsibility, but also with great fallibility. The entire world was made for us (humankind) AND we are but dust of the earth.

Judaism loves a good dialectic. Intersex justice loves a good both/and statement too; our intersex bodies and the basic fact of our entire existences defy the either/or male/female binary, a powerful dichotomy that looms over us from our earliest moments on this earth. It’s up to each person to commit, and recommit each day, to the ongoing personal journey of internalizing and embodying ethical values – especially the dialectics and both/ands.

There are Rabbinic interpretations which condone and even encourage surgeries and other procedures so that intersex people fit the sex binary. I made the decision not to include them here. These interpretations assume that the dominant medical and social-political narratives of their time were the accurate rule. While guided by Jewish ethics, they were also guided by historical and political contexts of intersex, transgender, and queer erasure. As a result, their interpretations cannot be used to define a concrete Jewish-ethical take on the gender-sex binaries and intersex rights.

On Being a Bystander

Hillel the Elder – b. 10th century Babylon, d. Jerusalem, Roman Judea

… If I am not for myself, who is for me? But if I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?

This passage cites Hillel the Elder, a sage and Jewish religious leader who lived before the time of Rabbinic Judaism and familiar clergy structure. Hillel taught that we must seek to strike a balance between self-advocacy and allyship. It’s not enough to act only in your own interests; you must also work for the benefit of others. It’s important to find the balance in order to avoid activism burnout but also in order to create the most impactful lasting change.

Everyone’s structure of socialization and solitude looks different. Some of us need more me-time, while others are energized by engaging and organizing with their peers. Go with your gut. Check in with yourself and your values. If you wait for the perfect moment to take a leap or make a change, you’ll miss your chance as the moment flies by. Similarly, if you wait too long to engage in rest and self care, you’ll burn out and be unable to realize your goals. Don’t act on impulse, but don’t wait for time to pass you by. Like I said, Judaism – and Jewish ethics especially – love a good dialectic.

In a place where there are no menschen, strive to be a mensch.

A mensch is the traditional yiddish word for a person who acts with integrity and honor. From their youngest days, Jewish children are taught to embody prosocial character traits like kindness, generosity, truthfulness, and a mind for doing what’s right. Personally, I feel the lesson of menschlichkeit (mensch-ness) about as deep in my soul as V’ahavta L’reacha Kamocha. Jewish tradition teaches that even if everyone around you is acting without morality, you have the power, and even the responsibility, to do what’s ethically just.

On the “Greater Good”

That which is hateful to you do not do to another; that is the entire Torah, and the rest is its interpretation.

In another story of Hillel the Elder, a man considering conversion to Judaism offers a challenge: if Hillel could teach the man the entire Torah – the whole Jewish tradition – while he stood on one foot, the man would be convinced to convert. In practice, conversion is much more complex, but nonetheless, Hillel took the challenge. He shared a version of the golden rule, saying simply: “that which is hateful to you do not do to another.” The rest, Hillel says, is just commentary. That’s Jewish ethics in a nutshell; act from love, not from hate.

I think of this adage often in the contexts of social justice, liberation and morality. Like most ethical statements packed into a single sentence, it’s more complicated in practice. The right and wrong ways to act are not typically so clear, but to me, one thing absolutely is clear: Hate suffocates; love expands.

[Rabbi Tarfon] used to say: It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it.

This work – activism, advocacy – is hard. None of us can do it alone and no one person will solve world peace. The work is not yours alone and you are not required to do the most all the time. A person can’t control or change your past experiences, but they can seek out new experiences and reputable sources of information. You may not have known a certain perspective or nuance before, but once you know better, you can – you need to – do better. Applying this dialectical maxim to the context of intersex justice; now that modern medicine knows better, Judaism calls upon us to demand medicine to recognize and do better.

| Devarim (Deuteronomy) 16:20

Justice, justice shall you pursue, that you may thrive and occupy the land that the LORD your G-d is giving you. |

דברים ט״ז:כ׳

צֶ֥דֶק צֶ֖דֶק תִּרְדֹּ֑ף לְמַ֤עַן תִּֽחְיֶה֙ וְיָרַשְׁתָּ֣ אֶת־הָאָ֔רֶץ אֲשֶׁר־ה׳ אֱלֹקיךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לָֽךְ׃ (ס) |

The journey toward justice never ends. There is always more work to be done, more progress to be made, deeper liberation to seek out. Such is the plight, and beauty, of humanity. Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1993-2020) z”l, the Notorious RBG****, the Supreme Court Justice and legislative powerhouse who needs no introduction, embodied menschlichkeit, Jewish ethics, social justice in a way I can only strive to honor. She borrowed from this passage for the title of her final earthside work, Justice, Justice, Thou Shalt Pursue. The fight for intersex rights, and other social justice liberation movements, are intertwined and are forever.

Judaism says #EndIntersexSurgery:

Gray Matter III, Medical Issues, Cosmetic Surgery, A Review of Four Classic Teshuvot

Rav Waldenberg forcefully argues that the divine license to heal applies only to curing an illness, not to altering one’s appearance. It is certainly forbidden, he adds, to risk one’s life to undergo cosmetic surgery, even if the risk is not great… In another responsum, Rav Waldenberg addresses the permissibility of undergoing elective surgery on a Thursday or a Friday. While the questioner was primarily concerned about the surgery interfering with Shabbat observance and enjoyment, Rav Waldenberg simply responds that Halachah never condones elective surgery. If a surgery is not necessary, it may not be undertaken.

Intersex genital surgeries and hormonal interventions, motivated by the stronghold of the false sex binary, are cosmetic and medically unnecessary – especially when performed on infants and children. When a person grows into their gender identity and relationship to their sex characteristics, they can make informed choices about what, if any, gender-affirming care is appropriate for them.

Interventions like hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and gender-affirming surgery should not be considered halachically-cosmetic; they are as vital and necessary to the health of a person’s body and soul (neshama) as any other ethical medical intervention. Jewish ethics both the psychological and physical health of an individual with the utmost priority, detailed in the halacha (Jewish law) of pikuach nefesh, preservation of life. Judaism values informed consent, ethical medical care, and bodily autonomy.

SVARA’s Tefilat Trans: Blessings and Rituals for Trans Lives features blessings for moments throughout an individual’s journey of sex- and gender- affirming actualization. There are bright, vibrant Jewish communities across the denominational spectrum embodying the Jewish values of chesed (lovingkindness – for oneself and others), kavod (respect – for oneself and others), and tikkun olam (healing the world).

On Allyship

At a time when the community is suffering, no one should say, “I will go home, eat, drink, and be at peace with myself.”

As members of a global community, Jewish ethics believe that there is a collective responsibility to care for our fellow humans, within our local communities and beyond. So what should be done when you see injustice, but it doesn’t impact your day-to-day life? Some might crave to stick their head in the sand, deciding that because they have the privilege of circumstance to not experience a certain oppression, that the particular oppression doesn’t exist. I don’t believe that’s the answer, immediately gratifying as it may be.

Intersex rights are not just an intersex issue, or a queer issue, or a medical issue. They are an everybody issue. Every one of us deserves bodily autonomy and every human benefits from sex- and gender-affirming care. (Spoiler: Many cisgender and endosex people take hormone replacement therapy and androgen blockers too.)

While a healthy news diet and sufficient coping skills are absolutely vital in a chaotic ever-changing world, you also may not ignore a community that is suffering. At the end of the day, humanity is a collective, however divided politics or proverbial-powers-that-be might make it seem. Jewish ethics require us to be socially responsible and active in social justice in our communities, even if a particular issue doesn’t affect you majorly or personally.

You may not be a bystander. As was said by 19th century author, poet, and activist Emma Lazarus, drawing from the lessons of Jewish ethics, “Until we are all free, we are none of us free.” The fight for bodily autonomy, liberation, and self-actualization did not begin, nor does it end, with intersex rights. Autonomy, liberation, and peace (shalom in Hebrew), are attainable only when we stand together – kulanu b’yachad.

INTERSEX ALLYSHIP 101

Each one, teach one.

Now you know about Jewish ethics, social justice, and intersex rights! These texts and ethics can be applied to many social justice topics – take it and run! Your Judaism and your social justice is yours. You are competent, capable, and divine just by being human.

Listen to our stories and amplify our voices.

Attend intersex events, interact with advocates on social media, and shop queer and intersex artists and small businesses. The more interaction with the intersex community, the more aware and inclusive our world becomes.

No Pride without the “I”

Don’t forget to use the entire LGBTQIA+ acronym – even if someone says it’s alphabet soup! We’re there for a reason. Often, places that say they’re LGBT or even LGBTQIA+ affirming don’t consider the intersex perspective. Use the intersex inclusive progress flag and encourage any queer-affirming efforts to do the same!

VOTE and engage politically.

An intersectional feminist adage, taught to me by Dr. Nyasha Grayman-Simpson, Associate Professor of Psychology and Africana Studies at Goucher College; “the personal is political.” If the personal hasn’t become political for you, just you wait. If you have the luxury of your basic human rights never having been up for debate by legislators and at the mercy of American voters – that’s privilege – privilege you can use to advocate for oppressed groups in spaces their voices might not otherwise be heard.

Voting and political engagement are how the most concrete change is realized. The intersex community stands in firm solidarity with the transgender+ community. Anti-trans legislation and restrictions on gender affirming care hurt us all.

In 2023, more than 65% of state-level bills proposing a ban on gender-affirming care included explicit stipulations which would force the same treatments they restrict for trans folks, who ask for them with informed consent, onto intersex people without their consent.

If that sounds wild, it’s because it is. These bills are not – and never were – about providing quality healthcare to children who are intersex, transgender, two-spirit, and gender non-conforming. It was always about forcing “healthcare” on children and adults for the sake of perpetuating sex and gender binaries based on eurocentric western-supremacist ideals. I hesitate to even call it health or care if it’s done without informed consent.

Judaism values a concept known as l’dor v’dor – from generation to generation. L’dor v’dor means that we work hard today not just to create positive change now, but to make drops in the ocean of justice that ripple for years to come. For thousands of years, through eras of persecution and diaspora, not unlike those of any other marginalized group, Jewish families have resiliently embodied and bequeathed from generation to generation the ethics and values I explored above. The intersex community – and other marginalized communities – need allyship and solidarity to create a better and more just future for the next generations.

TO END WITH A PRAYER

When I first began to show characteristics that didn’t align with the puberty of my assigned sex at birth, I thought I was the only one in the world having such an alienating experience. My body wasn’t talked about in early 2010’s middle school sex ed. Every article and video I saw online told me that I was nothing more than a broken female body, destined for a life of chasing a body I could never have. Even once I came to the understanding that I might be intersex, resources online were so sparse that I believed I was the only person who thought my variation counted under the intersex umbrella.

Oh, how badly I wish I could tell tween and teenage Liat she was so wrong. It was no use chasing a hairless, hourglass-shaped, feminine body I could never have, because I was never meant to exist in that kind of body. There’s a growing wealth of up-to-date, accurate, affirming information out there for intersex youth and their families today, and I feel blessed to contribute toward the next generation of youth growing up Jewish, intersex, queer, or any of the above.

The answers to our future lie in the foundation of liberation movements in decades gone by and in the study of our pasts. Like the Torah says, there is nothing new under the sun. Every question I’ve asked and every struggle I’ve struggled – someone, somewhere, in some way, asked the same one or struggled in a comparable way.

When I met other intersex people in person for the first time this summer at the InterConnect conference, I found community and healing in the common experiences of people both with my intersex variation and with other variations. I thought I was alone when in fact I never was; my intersex peers and my intersex elders – my Jewish elders too – were always there, even if I didn’t know it quite yet.

When I wind down for the day or watch the sun set below an emerging evening sky, it reminds me that somewhere across the world, somebody else is watching the same sun rise above the same horizon, the world softly awakening them for another day. Perhaps we’re both looking for the same things in the divine changing light – wisdom, a wish, realization of a dream.

For a moment, I remember that myself and this nonspecific fellow human are alike more than we are different, going about our not-so-silly silly little lives under the same sun and moon and stars, under the same sky, in the same vastly infinite universe.

For a moment, the rest of humanity and I are not so far apart. Our rights are the same rights and our home is the same home. Our sex, gender, and other diversities are uniquely divine and our fights for a better world, absolutely intertwined.

Every morning as a child, and most mornings still today, alongside V’ahavta L’reacha Kamocha, I say Modeh Ani – a prayer recited every morning by Jewish people across the world in a variety of tunes, contexts, and intentions.

| Modeh Ani, Shacharit (Morning Prayer)

I give thanks to You, living and everlasting G-d, for You have restored my soul graciously. Great is Your faithfulness in me. |

מודה אני, שחרית

מוֹדֶה/דָה/דֶת אֲנִי לְפָנֶֽיךָ מֶֽלֶךְ חַי וְקַיָּם שֶׁהֶחֱזַֽרְתָּ בִּי נִשְׁמָתִי בְּחֶמְלָה, רַבָּה אֱמוּנָתֶֽךָ: |

Be they an omnipotent being or the intangible quality of divine ethereal natural energy, I thank Hashem – for the dear, dear earth, the sunshine (or the rain), and for another day with my intersex body and neshama (soul).

Happy intersex holiday season to my fellow intersexies, and to the loved ones, allies, and strangers receiving this little piece of my human journey – thank you.

FOOTNOTES

*Many Jewish authors have the custom to write “G-d” instead of “G-o-d” so as to avoid writing G-d’s name and the possibility of needing to subsequently erase or destroy it.

**For more on this historical context, I recommend The Spectrum of Sex by Hida Viloria, Maria Nieto, et. al..

***A note on the use of DSD – Disorder/Difference of Sexual Development: Whether the first D stands for disorder or difference, this term is considered offensive to the intersex community. The term posits intersex bodies as pathologies to be fixed instead of as natural variations of the spectrum of human sexuality.

****A nickname coined by intersexcellent lawyer, Consulting Producer on Every Body, and overall awesome human Shana Knizhnik.

FURTHER READING & RESOURCES

Organizations

Watch List

Every Body (2023)

Buzzfeed – What It’s Like to Be Intersex (2015)

Intersexion (2012)

Orchids: My Intersex Adventure (2011)

Reading List

The Spectrum of Sex: The Science of Male, Female and Intersex, (2020), Hida Viloria, Maria Nieto, et.al.

Nobody Needs to Know (2023) – Pidgeon Pagonis

Inverse Cowgirl (2023) – Alicia Roth Weigel

Not Uncommon, Just Unheard Of (2023) – Esther Leidolf

XOXY (2020) – Kimberly Zeiselman

Intersex (For Lack of a Better Word) (2008) – Thea Hillman

Born Both: An Intersex Life (2017) – Hida Viloria

Liat Feller, 2023