June is CAH Awareness Month. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia is the medical term given to one of the most common intersex conditions. We talked to five young people about their experiences with CAH, adrenal crisis, and growing up with intersex bodies.

By Bria Brown-King

This essay is also available in Spanish, thanks to the translation of Laura of Brújula Intersexual: “5 personas intersexuales hablan sobre crecer con Hiperplasia Suprarrenal Congénita”

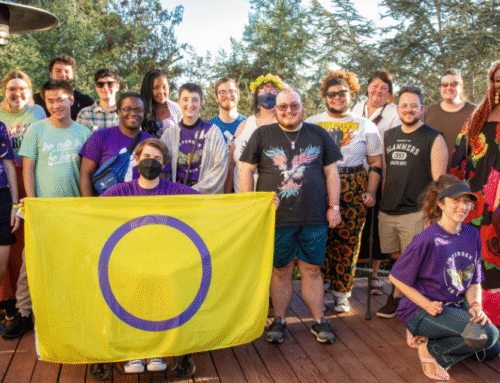

Five intersex Youth advocates, from left to right: Allie (they/them), Jubi (they/them), Mari (they/them), Bria (they/she), Sophia (she/her)

How did you learn that you have CAH and how old were you?

Allie: I found out that I had precocious puberty when I was 6. I started getting signs of puberty when I was 6 and my pediatrician referred me to an endocrinologist after I started growing dark and thick body hair. I received the official test at 7. My mother was always open with me regarding my diagnosis.

Jubi: I heard the term CAH for the first time when I was already 22 years old, desperately searching Google for others who shared the same traits I had. I was newly homeless without access to regular healthcare, but needed answers. While searching the internet an image caught my eye, text underneath sounded like it could’ve been my autobiography, down to the smallest details about everything I’d blamed myself for: the puberty, hormonal complications—the coincidences were extreme. That probably doesn’t sound like a serendipitous revelation, but after a lifetime of fearing I was the only one with a body like mine, suddenly I had the confidence to live my truth instead of hiding it.

Mari: Though I began to question my body at an early age, I didn’t have the vocabulary to describe my experience until I first mentioned my symptoms to one of my doctors when I was 18. I was diagnosed with PCOS, but at that point the word “intersex” was never used and I was never able to access resources within the intersex community. Around age 21 I pushed for more extensive blood work because I felt that I was easily dismissed early on—at which point I was diagnosed with non-classic CAH or NCAH.

Finding out that I am actually a part of the CAH community has allowed me to find so many other people with similar experiences, and has helped me understand more about my body. Additionally, I find that sharing my story of both misdiagnosis and diagnosis as an adult helps to normalize the experience of not discovering one’s intersex variation until later in life.

Bria: The earliest memory that I have is going to visit my endocrinologist when I was 3 years old. I was too young to understand what CAH meant in terms of my body, but I knew it was the reason I had to take my medicine 3 times per day. I didn’t question any of it as a kid, I just did as my mom and my doctors told me.

Sophia: I was 16 when I learned that I have CAH. My body started changing around fifth grade but didn’t pursue answers until I was in high school. I still hadn’t gotten my period or grown breasts and my body and facial hair was thick and dark. My pediatrician and gynecologist both ran tests and didn’t find anything. My doctor referred me to an endocrinologist who almost didn’t find anything – until she thought to run an ACTH stimulation test, which confirmed a diagnosis of non-classic CAH.

When you were growing up, what was it like to find out that your body was different?

Allie: It was scary at first. I had thoughts of “why me,” “why am I different,” “am I supposed to feel bad about this?” I was fortunate that I had a mother who told me that this was something that I could be proud of. Every summer I’d go to a convention with other kids that had endocrine issues. This helped me realize that I wasn’t alone. It was still isolating because I didn’t meet anyone else with my specific type of CAH. Everyone shared their specific CAH variation, and they all had Steroid 21-hydroxylase. We need to have more conversations about the different types of CAH, because we are not a monolith.

I knew other girls didn’t grow facial or body hair like me, but I didn’t understand why.

Jubi: Alienating. I became a survivor of childhood sexual abuse very early on, so by the time my body developed, it made sense in my childhood mind that I was at fault for the changes. My secrets grew into shame. I hid my assaults along with my precocious puberty from my friends and family, hoping ignorance would be bliss. When I was 14 years old and didn’t have my period, my doctor prescribed me estrogen, which caused hemorrhaging. I was given an exploratory surgery for “endometriosis.” Instead, no endometriosis was found and tissue from my gonads was taken out in secret. Even the relationship I had with my long-term high school sweetheart suffered as I struggled to have penetrative sex. I tried to compensate for my masculine traits by wearing makeup and mile-high shapewear to ease my agonizing sense of dysphoria.

Mari: Finding out that my body was different was originally a very isolating experience. When I was questioning myself and my differences the most, there wasn’t a lot of information out there to help me understand what I was experiencing. At the same time, finding out that my body was different and that it exists outside of the sex binary was also a healing experience for me, as someone who identifies as nonbinary. I found that growing up, my body aligned with my understanding of my gender, which allowed me to explore my gender better than I believe I would have been able to otherwise.

Bria: I didn’t know that my body was different until other people made me aware of it. I started growing facial and body hair when I was about 6 or 7, but didn’t pay it any mind until other kids started pointing out the differences and bullying me because of it.

My doctors and my family kept telling me that I was a normal girl, but I knew that I wasn’t. It felt like everyone was ignoring how different I was and that was frustrating. I became extremely depressed and I had so much anxiety because everywhere I went people acknowledged those differences. It felt like the more I tried to be “normal,” the more I stood out.

Sophia: Truthfully, I felt very ashamed of my body growing up. I knew other girls didn’t grow facial or body hair like me, but I didn’t understand why. Classmates called me “man voice” and made fun of my flat chest and muscular arms. I woke up two hours early every morning to make sure I had time to remove every visible hair from my face, all for fear of someone catching a glimpse of my stubble. I didn’t actually notice the things that made my body different until other people pointed them out, and then it just stuck with me.

What does ‘intersex’ mean to you?

Allie: When I discovered the word ‘intersex’ it was like an aha moment. It was shocking and serendipitous. I was running a queer club in Montana. A member hosted an “Intersex 101” workshop, and that’s when I learned the second-most-common intersex variation is CAH. It was like a puzzle piece I didn’t know was missing, fell into place.

Jubi: To me, intersex means the natural infinity beyond the sex binary. Individuals with intersex traits can’t be easily categorized as having typical binary “male” or “female” sex characteristics. Intersex variations are examples of human diversity in nature, and nature does not exist in a sexual dichotomy. The word ‘intersex’ changed my entire sense of self and put a loving community behind my back.

Finding the term “intersex” and finding the intersex community helped me realize that not only am I not alone—I am normal and my body is natural.

Mari: To me, ‘intersex’ means that I am not alone. Before finding the intersex community, I felt like I was the only person in the world with my exact experience. It made me feel othered from those I considered “normal.” Finding the term “intersex” and finding the intersex community helped me realize that not only am I not alone—I am normal and my body is natural.

Bria: To me, intersex means finally having a word to describe my experience and my body. I learned the word intersex when I was about 13. I was desperate to learn more about my body. I think that intersex also means community.

Sophia: ‘Intersex’ captures my experience in a way that a medical diagnosis cannot. Discovering I’m intersex and finding community online was so important in beginning to heal from the confusion and shame I felt growing up. I didn’t learn about intersex, or that CAH is an intersex variation, until I was 20. I gained clarity and respect for my body by understanding it through an intersex lens that I wish I had been offered at a younger age.

Adrenal crisis is a very real fear for many in the CAH community. Is this something you have experienced?

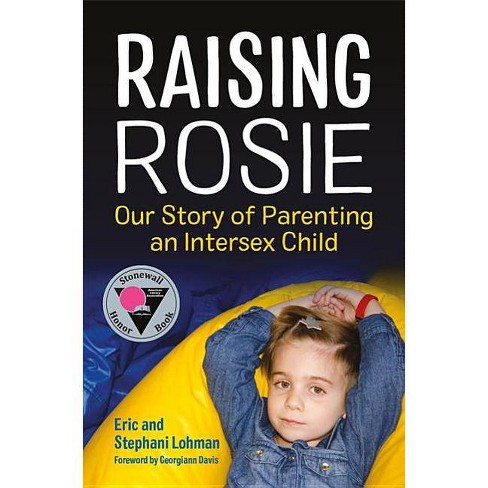

Raising Rosie, by Eric and Stephani Lohman, is a memoir and parenting guide. The book details how the family was pressured to choose clitoral and vaginal surgery for their newborn with congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Allie: For sure! I definitely have experienced many adrenal crises. I have a stomach disorder and it causes me to get sick a lot, which causes me to worry about having an adrenal crisis. I have to carry injectable hormones with me, and I keep instructions on how to handle a crisis if it happens and what medications I need.

Adrenal crises are definitely serious. We need to be better educated about them, especially emergency personnel. Most ambulances aren’t equipped with the steroid hormones a person with CAH would need during a crisis.

Jubi: I consider myself lucky enough not to have had a full-on adrenal crisis, but my adrenal insufficiencies have nearly cost me my life a handful of times. When I traveled across the country on my first flight, I went into shock so quickly that I developed a muscle breakdown and had to be hospitalized three times. I needed immediate rehydration and a pharmacy’s worth of medicine just to stay alive. It took me more than two weeks to recover.

Mari: As someone with non-classic CAH, adrenal crisis is not something that I have experienced. That said, I find it extremely important to be educated and to educate others on what adrenal crisis might look like.

Bria: My doctors thought that I had the type of salt-wasting CAH that could cause an adrenal crisis until I was 19. They later told me that I probably had another type of CAH. I’ve never experienced an adrenal crisis. However, I think it’s important to acknowledge how severe they are for many folks in the CAH community. I absolutely want CAHers with adrenal insufficiencies to get the support that they need to stay healthy.

Sophia: Thankfully I’ve never experienced an adrenal crisis, but it’s something I think about a lot.

Is there anything you’d like to say to other young people with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia?

Allie: There’s nothing to be ashamed of. This is the moment. This is our moment!

Jubi: If you were like me and grew up without a medical diagnosis due to poverty and abuse, you might’ve blamed yourself for the way your body developed. It’s not your fault—there is no wrong way to have a body. You deserve the privilege of loving your body and the way it works.

Mari: If there’s one thing I could say to a young person with CAH, it would be, “your body is yours and yours alone.” With the way the media debates whether or not intersex people deserve bodily autonomy, it’s extremely important to remind every person that they deserve to exist in their body exactly as they are. I would also say, “Those of us in the intersex community welcome you with open arms.” Despite what others might say, being intersex is your experience and you have a place in our community.

Bria: My friends, you are so brave. You’re not alone. If people tell you that your body is different, don’t take that as an insult. Maybe one day you can use those critiques as a way to educate the world on why being different makes you unique and beautiful.

Sophia: It’s important to remember that you know your body best, and you are your own best advocate. I know this sounds corny, but I believe it—your body is perfect, and your greatest power is in reminding yourself of that every day.

These interviews were conducted over phone and email, with minor edits for length and clarity.