Apollo grew up with a variation in sex traits typically associated with women — MRKH — but knew he was a man. At times, his intersex variation was a relief. At others, being one of the only men with MRKH was profoundly isolating. But MRKH is a part of him, and he loves it. Read more of his story below, and learn more about MRKH in our variations glossary.

A still image of Matt Bellamy, the lead singer of Muse, falling downward into outer space.

My birthday was 3 weeks late.

When the delivery date passed by, and the days turned into weeks, an ultrasound was scheduled. During that appointment, it was discovered that I was missing a kidney. This revelation was quite the shock, to say the least.

When I was finally born, another surprise happened: “Jack” no longer quite fit the expectations of what my parents thought my future would look like, so they struggled to choose an alternative, more feminine name on short notice. As an extra bonus, I also failed the newborn hearing test.

In exchange for these subverted expectations, the first seven years of my life were filled with medical assessments that sought to uncover their origin. Audiometric and BAER testing, karyotype analysis, transabdominal ultrasounds, a cystoscopy, a pelvic MRI, an echocardiogram, and further genetics testing.

You know what I do remember instead? I remember the smell of the cigarettes my nana used to smoke as we sat together on her back porch watching the Kentucky sunset. I remember how the long road trips always felt worth the comfort of visiting her and my papa.

In the end, it seems that I was confidently diagnosed with MRKH at around 6 years old. I had barely finished first grade at this point, so I don’t remember much from these procedures. Maybe it’s because around this time, my parents decided to stop taking me to so many diagnostic medical appointments. My pediatrician’s supportive and non-pathologizing approach that revolved around the concept of, “Your kid is just a different type of normal,” definitely had an effect on them. They wanted me to have as typical of a childhood as possible, especially since I had no pressing health concerns beyond profound deafness and renal agenesis, so you know what I do remember instead?

I remember the smell of the cigarettes my nana used to smoke as we sat together on her back porch watching the Kentucky sunset. I remember how the long road trips always felt worth the comfort of visiting her and my papa.

I remember the books and video games with fictional worlds so captivating that I couldn’t put them down.

I remember playing hide-and-seek and four square with the neighborhood kids late into the summer evenings. I remember the countless block parties and birthday sleepovers.

I remember developing a love for gardening with my mom. I’d help guide jackmanii clematis vines up the backyard trellis every spring and summer afternoon when I’d water the flowers in our gardens.

I remember being a Girl Scout—Brownie, Junior, and Cadette. I remember making and trading “SWAPS” at summer camps. I remember sending emails to keep in touch with the variety of friends I’d made.

In the midst of all these happy childhood memories, there is one particular medical appointment that stands out the most. At age 9, a pediatric MRKH specialist told me how my internal reproductive anatomy was different than I might expect… and I remember how utterly inconsequential these details felt to me.

I already knew I was “different”. My deafness isolated me from my peers—creating auditory processing issues that left me with listening fatigue after the end of each school day—and my neurodivergency posed a challenging barrier to learning initial social skills.

At age 9, a pediatric MRKH specialist told me how my internal reproductive anatomy was different than I might expect… and I remember how utterly inconsequential these details felt to me.

So, what difference did having MRKH make? Well, apparently, there was a big difference right around the corner. However, when my peers began to discuss the experiences tied to menstrual cycles, I frequently sighed with relief that this would never be a concern for me.

Even as we began to learn about reproductive health in school—with no mention of diverse sex characteristics in the coursework—my MRKH felt like a secret that didn’t actually hurt to keep. While a few of my friends did in fact know, they either responded with supportive ambivalence or a respectful curiosity.

Although, I never knew anyone with MRKH until I was 15 years old. I remember the excitement before the 9th annual MRKH conference for teens and their families in Boston… and how it turned to disbelief when I learned that I was the only teenager there out of 20 who had been screened for and diagnosed with MRKH pre-puberty. I felt like an incredibly rare exception in the demographics of MRKH at the time.

Our time together in high school ended with two very distinctive achievements on the night of our senior prom: she had won Prom Queen, and it was the last time I ever wore a dress.

However, I’d never known anything different, so my attention largely gravitated away from MRKH and toward a new friend I’d made. They were someone who shared a lot of similar interests with me, and we were planning to keep in touch.

I somehow continued to know more people with MRKH, though, after that conference. It was less than a year later that I found out my best friend was recently diagnosed with MRKH, and how her feelings toward that information were so very different from mine.

Interestingly, our time together in high school ended with two very distinctive achievements on the night of our senior prom: she had won Prom Queen, and it was the last time I ever wore a dress.

Thankfully, I got a second chance to wear masculine formalwear to prom when my university’s queer organization held an event for the people who couldn’t be themselves at their high schools.

My complete acceptance of MRKH making me “different” had eclipsed my gender dysphoria, so I didn’t expect the realization at age 17 that I wasn’t cisgender, but that lightbulb moment illuminated so many of my confusing emotions and experiences. It brought so much relief and understanding.

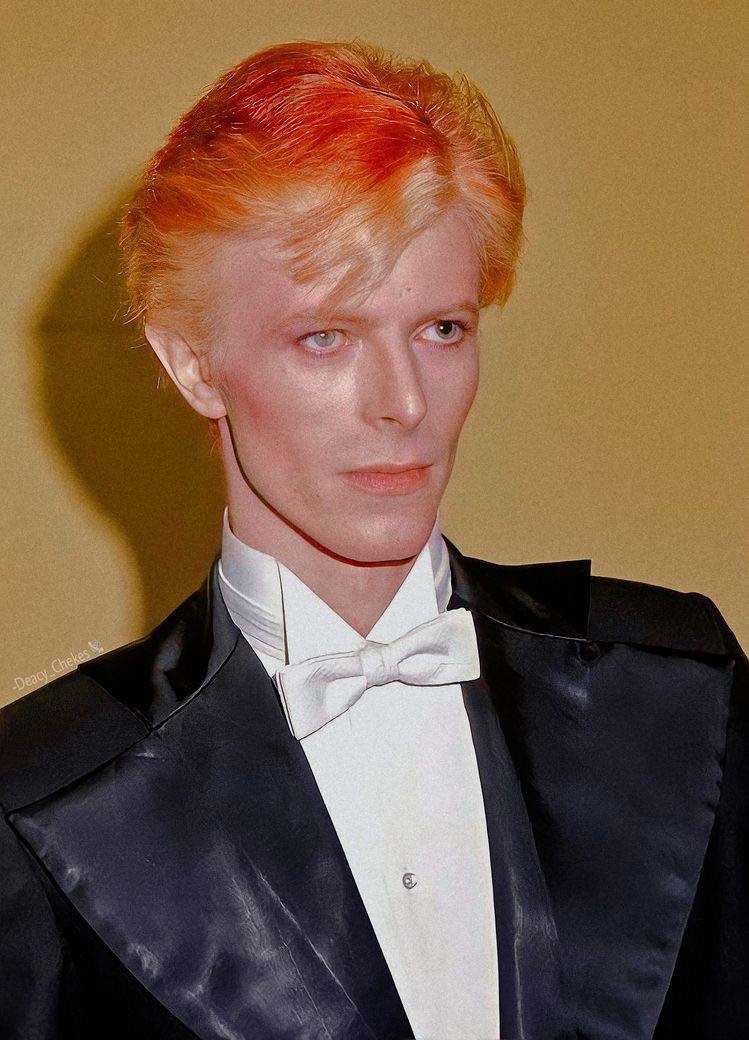

However, it didn’t give me a complete answer for what came next in my life, so I spent time exploring my gender expression at university. In the end, the masculinity of David Bowie revealed itself as my muse for my future.

I realized that there was a whole realm of possibilities for me to explore with my gender identity—a whole new frontier—and masculinity seemed to be the way forward for myself. So, I took a small step for man, and made a giant leap into the sublime unknown. While not everything was smooth sailing, I have never regretted my decisions to socially, medically, and legally transition.

As I’ve settled into my body more and more with each passing year, I recall my parents telling me how much they had worried about the knowledge of my MRKH negatively affecting me… but instead, I accepted it with no trouble at all. MRKH was not a rogue comet that destabilized my orbit, but rather a natural satellite. MRKH is just part of who I am, and I wouldn’t be the man I am today without it.

I’m grateful for how my body has defied expectations from the very beginning, so I’ll leave you—dear reader—with a song that utterly represents how happy I am to be myself.

interACT believes every intersex person deserves justice, and that only through ending interphobic legislation and intersex medical harm can we find justice under the law. You can help create a different future for intersex youth by giving here.